Energy Security Intelligence Research

ESIR

ESG STRATEGY RISK and COMPLIANCE PLANNING AGENDA 2050

UNITED-KINGDOM

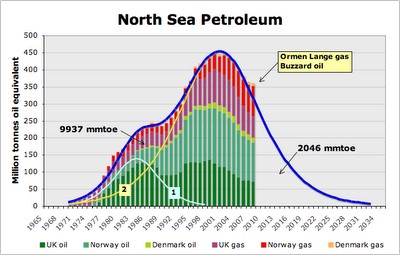

The UK's Offshore oil and gas bonanza has been an amazing success story: it contributed enormously to the national wealth and even made the country self-sufficient for over four decades of time. The UK was a net exporter of oil for some 25 years until 2005 and for a shorter period it also produced more gas than it could consume, at a time when gas demand was at its peak. So far the country has produced over 42 billion barrels of oil equivalent from 1974-2005.

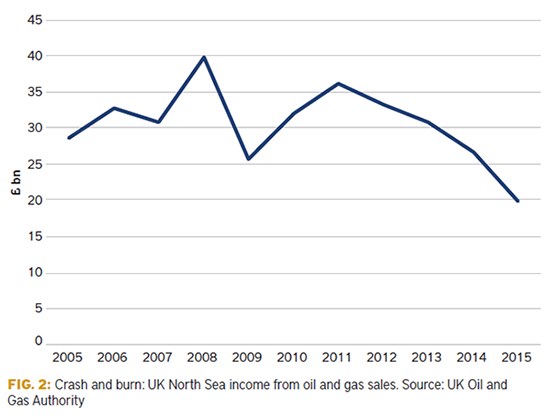

Even now the industry supports the employment of some 450,000 people and underpins the export of related goods and services worth £7bn. For example, in 2012-13 the industry paid £6.5bn in corporation tax and made a contribution of £39bn to the national balance of payments. But there is no denying that the oil and gas reserves are coming to the end of their lives and now attention has turned to squeezing out the last drops of oil and diversifying to unconventional sources like shale gas.

Things were relatively straightforward in the early days offshore when a small number of very large oil and gas fields dominated UK production. But now there are over 300 fields, some of which are small and whose output depends on other fields' facilities for access to market. The UK produces oil mainly from the North Sea Central Graben area, close to the median line with Norway. There are two main clusters: one is around the Forties oilfields east of Aberdeen which at its peak produced 500,000 barrels/day under BP's operatorship; and the other is east of Shetland, home to the Brent field.

That field provided the crude stream that was prolific enough to become a global oil price benchmark. Depletion has taken its toll so it is now much diluted with crude from other fields in Norway-including Forties and, across the median line, Oseberg and Ekofisk. On the gas side, imports from Norway once accounted for a quarter of UK demand and the UK was also the world's first importer of Algeria LNG.

"As the typical discovery size shrinks and costs remain high, fewer wells are being drilled; and companies are deferring their more expensive projects"

The UK also enjoyed a brief period as gas exporter, after the first pipeline to the outside world-the bi-directional UK-Belgium Interconnector-opened up in 1998. That helped fuel the rise in gas production-aided by the government of the day ending British Gas twin monopolies on gas purchasing and retail supply. The resultant free-for-all in the downstream market cut prices as producers formed downstream marketing alliances and led to a dash-for-gas in the power generation sector. But as an oil and gas exploration and production province, the easy gains have been exhausted and the UK Continental Shelf has been sliding into decline for a decade or more.

However, there is still some upside, thanks to technology, improvements in efficiency, and changes to the tax regime that can make viable fields that were formerly not worth the cost. A case in point is Engie's Cygnus gasfield, which is due to start producing in 2017. But the typical discovery size shrinks and costs remain high, fewer wells are being drilled; and companies are deferring their more expensive projects.

North Sea struggles in a new era

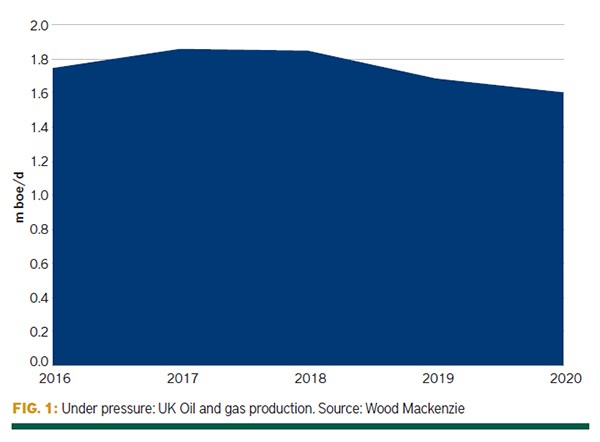

UK North Sea projects coming on stream in 2017 will add fresh output, but this activity can't mask the underlying lack of upstream investment appetite. Even a firming of the oil price doesn't look likely to change this.

The near-term outlook is more positive than it has been for some time. Both oil and, to a lesser extent, gas production were higher last year (2016) than the industry expected, and will lift output estimates for the next few years. But the overall trajectory is still downwards and output is already a fraction of its level 20 years ago. Meanwhile, seven North Sea projects should come online this year (2017), adding around 100,000 barrels of oil equivalent a day as they ramp up. The projects were all sanctioned between 2010 and 2014, before prices slumped.

"Higher oil prices would help, but they won’t restore glory to an increasingly marginal play"

Among the biggest, with 50,000 b/d of peak production, is Kraken, 70.5% owned by EnQuest. It is a typical modern North Sea development-the oilfield is heavy and its operator is struggling to stay afloat. EnQuest decided on the project when oil prices were twice today's level. First oil can't come a moment too soon for the company, whose floating, production and storage offshore (FPSO) vessel, the Armada Kraken, was expected on the field in late January 2017.

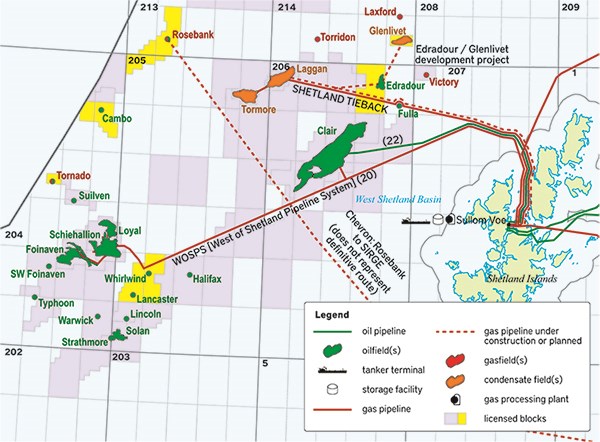

Premier Oil, another cash-strapped company, expects its Catcher project to come on stream in the second half of 2017 and produce 50,000 b/d at peak. Elsewhere, BP's Quad 204 project, incorporating the Schiehallion and Loyal fields in the West of Shetland area, is due back online having been closed for redevelopment since 2013, as a larger FPSO was put in place. An extension to Total's Laggan-Tormore project, also West of Shetland, which started production in early 2016, should also add output during 2017.

The government has implemented measures broadly welcomed by an industry eager for any help. The tax burden on North Sea E&P companies has been lightened, while the recently created Oil & Gas Authority has helped to streamline regulation and licensing and can take a more hands-on approach to reviving the industry than its predecessor.

Beyond this wave of projects, the outlook for new production is uncertain, though some sizeable developments could go ahead in the medium-term if conditions permit. Two or three fresh projects are scheduled to be sanctioned this year, though these remain tentative.

Hurricane Energy says its Lancaster and Lincoln finds on the Rona Ridge, West of Shetland, could hold more than 0.5bn barrels. The UK-based firm hopes to give the go ahead for a partial development of the Lancaster field before end-June 2017-these prospects received a boost with a 100m-barrel upgrade to the resource estimate for Lincoln (now 250m barrels)-which triggered a sharp rise in its shares in December 2016.

Alpha Petroleum is hoping to go ahead with its Cheviot field project, a redevelopment of the Emerald field discovered in the 1970s east of the Shetland Islands, which is estimated to have over 75m boe of recoverable reserves of oil and gas.

Premier should also move forward with another project, the Tolmount gasfield in the southern North Sea, which it took a 50% stake and operatorship in when it bought EOn UK in 2016. The field complex is estimated to hold resources of around 1 trillion cubic feet. If the decision to invest is taken in 2017, first gas is expected in 2019 or 2020.

Big projects struggle

But several large-scale projects have fallen off the radar, hobbled by high costs that put their breakevens well above the prevailing oil price of the past year. Operators have been left seeking cheaper solutions, delaying their schedules.

Some notable casualties have been in areas offering the greatest promise too. Xcite Energy's plans soon to develop the Bentley heavy oilfield, east of Shetland, have all but vanished after the company failed to find a partner. Bentley aimed to produce 0.7bn barrels over more than three decades, making it one of the North Sea's larger untapped developments. In 2014, BG delayed development of the Jackdaw find in the central North Sea, a high-pressure high-temperature (HPHT) project. Since Shell's takeover of the company, the project remains on hold.

The bigger the project, the higher the upfront investment needed. Smaller projects can keep costs down using existing infrastructure, so look more attractive to producers and investors.

"The trend is much more towards smaller subsea tie-backs," says Mhairidh Evans, a UK upstream oil and gas analyst at consultancy Wood Mackenzie. "The average UK project approaching final investment decision in the next two years has only got about 30m barrels of reserves associated with it. While it's hard to get a big project sanctioned that needs $1bn-2bn of investment, smaller subsea tieback at $0.5bn is easier."

This trend is plain in the price needed for new projects. Wood Mackenzie estimates that at the end of 2014, only 60% of UK projects in the development pipeline had a breakeven of $60 a barrel or less. Now the figure is almost 90%-a consequence of the departure of some more costly projects and work done to lower costs on others. The company uses a 10% discount to calculate this.

The slowdown of mature fields' production means output from new ones should form a growing share of the overall figure. By 2020, Wood Mackenzie estimates, around 30% of UK oil and gas production could be coming from fields starting up from 2017.

But the oil price and investment climate will decide this. While the Opec deal seems to have put a floor in the price, the industry will remain wary of dusting off high-cost projects until oil has been trading comfortably above breakeven for some time. Even then, many firms will seek opportunities in less mature oil provinces.

So a higher oil price, while helpful, is no longer a panacea for the North Sea. Other factors will also hold sway, such as the deprecation of the pound against the dollar since the Brexit vote. UK operators tend to pay for services in sterling but earn revenue in dollars-so the pound's plunge has helped. How Brexit affects the overall business climate, especially in terms of trade with Europe-and in particular of gas-is by no means obvious yet.

Costs plunge

A marked fall in development and operating costs has also brought some cheer. Oil & Gas UK, the industry's lobby group, said in September that extraction costs had fallen 45% since 2014. Wood Mackenzie reckons supply-chain costs have dropped by 20-25% since that year. Last year, Premier said its capital expenditure on the Catcher project had dropped by around 20% to $1.8bn.

New developments, and those that have returned to the drawing board, can expect to eke out further savings by streamlining project designs and adopting cheaper options.

The Norwegian North Sea provides a blueprint for the UK. Projects like Statoil's Trestakk and Centrica's Oda have achieved cost reductions following in-house design revamps. Cheaper services have also chipped in.

In November, Statoil submitted a new development plan for Trestakk, located some 27km southeast of the Åsgard A platform, which nearly halved its forecast capex. Under the new design, the project will be tied back to the Åsgard A oil-production vessel, with output starting in 2019. Capex is now expected to be around $0.65bn compared to an original figure of around $1.15bn.

Torger Rød, Statoil's head of project development, says savings were achieved by working closely with partners and suppliers to select the best concept, while also increasing recoverable resources. The discovery, made in 1986, holds around 76m barrels of recoverable oil equivalent.

These projects were ideal for redesign, because they were in an early stage of development, as successful exploration moved into the front-end engineering and design phase.

"If you are much further on in the project, or have already sanctioned it, making savings is much more difficult," says Wood Mackenzie's Evans. "That such progress on costs has not been made in UK projects is not a reflection on the UK industry, but merely a reflection of the stages of projects in the UK's pipeline. Projects due to be sanctioned in the next year or two will be going through similar processes now."

Exploration hiatus

The prospect of leaner, meaner developments could stimulate an uptick in UK North Sea exploration, which fell to record lows in 2016. A trend towards companies selling prospective acreage at the pre-exploration stage to realise cash, rather than drilling wells themselves, has contributed to the slowdown.

Government efforts to interest investors in fresh acreage have also struggled. Still, more interest is expected in this year's 30th UK offshore-licensing round, which is focused on more mature and potentially lower-cost plays in the North Sea basin, rather than last year's 29th round, which tried to lure explorers to frontier plays. It received a lukewarm response.

The considerable spectre of decommissioning costs also now envelops all considerations of investment in the North Sea. By some estimates, the total bill could surpass $100bn. No new player wants to risk being left liable for the hefty costs of infrastructure decommissioning that may be only a decade away. So all mergers and acquisitions negotiations are complicated by the need for watertight agreements on such liabilities.

Despite the travails, fresh investors are still prepared to sink their money into the region, hoping to capitalise as others bail out. In December 2016, Israeli-based Delek Group bought a 13% stake in North Sea-driller Faroe Petroleum for £43m ($53m) from Dana Petroleum. Faroe's portfolio includes around 61m boe. The move strengthens Delek's interest in the basin, having taken a 20% stake in North Sea-focused Ithaca Energy in October 2015.

On the other side of the equation, Shell has been reducing its exposure to the North Sea. It has sacked 1,000 workers at its operations in the region since 2014 and put a host of assets up for sale. A package of North Sea assets, valued at up to $3.8bn, has been confirmed with the small private explorer, Chrysaor - backed by US private-equity firm EIG Global Energy Partners.

Shell insists that the North Sea will remain one of its core areas of activity and that projects such as Jackdaw will eventually come to fruition. BP echoes the sentiment-its chief executive Bob Dudley recently referred to the region as one of its "crown jewels".