Energy Security Intelligence Research

ESIR

ESG STRATEGY RISK and COMPLIANCE PLANNING AGENDA 2050

LIBYA

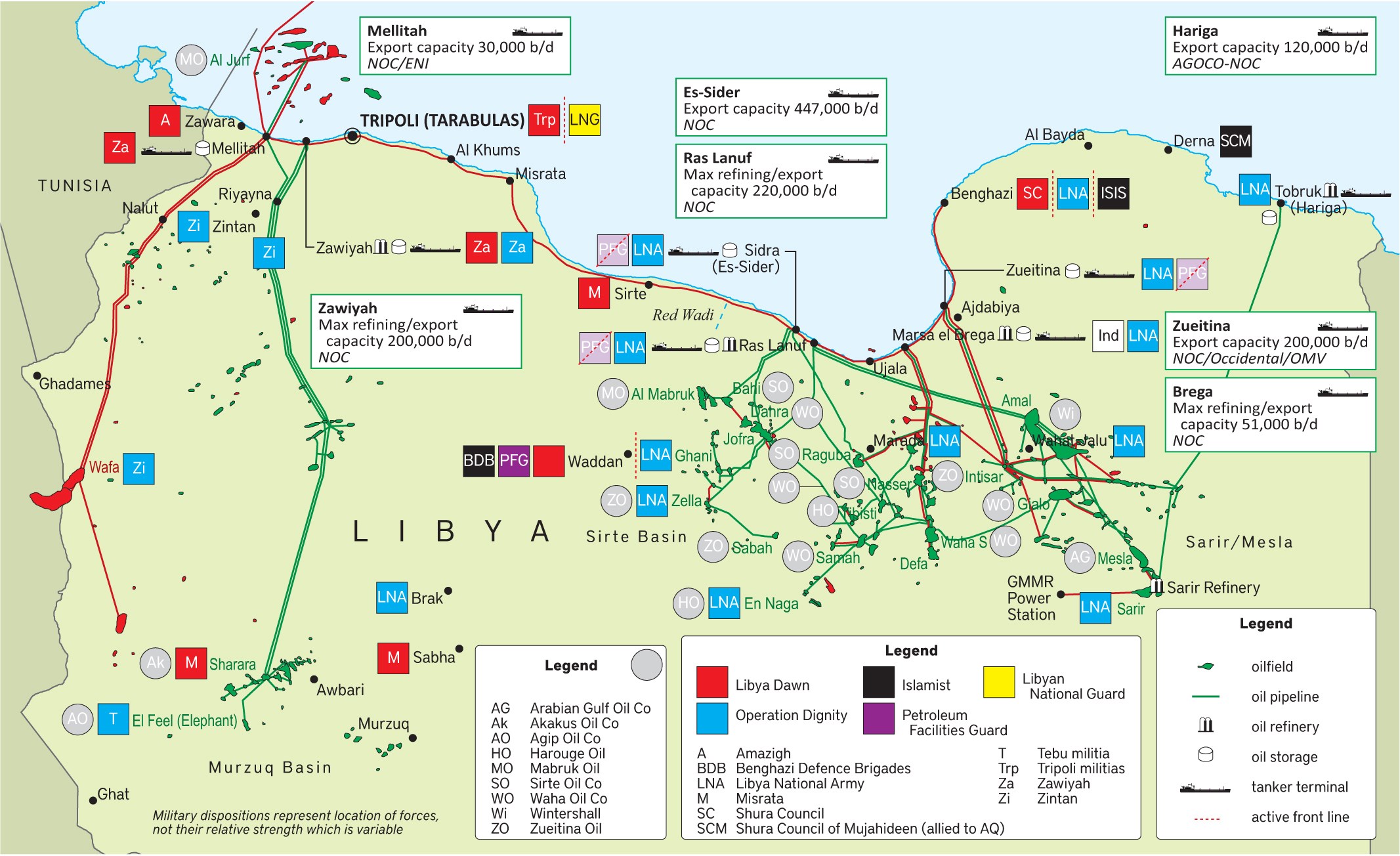

Libya holds Africa's largest oil reserves, and the bounty from production that, in peacetime, could reach 1.6m barrels-a-day is now again the focus of a civil war that has been raging for nearly two years. The trigger were elections for the House of Representative (HoR) in June 2014 that defeated the country's previous Islamist-led government. Proclaiming themselves the true guarantors of the 2011 revolution that overthrew Muammar Gaddafi, Islamists and their Misratan allies formed the Libya Dawn militia and captured Tripoli. The HoR fled the capital and relocated to Tobruk. War began.

Forbidden from selling crude itself, officials of the Tobruk parliament, the House of Representatives, have since announced a total blockade on oil sales, cutting Libya's exports by two thirds. Simultaneously, its forces launched an ambitious offensive to take control of the oil Crescent-the Sirte basin-home to two thirds of Libya's production capacity.

Libya's political chaos deepens

A new offensive by Islamist militias to capture Libya's eastern oilfields has set back the state oil company's hopes that foreign firms will return to the country's upstream - and creates new doubts about its ability to sustain an oil-output recovery.

The Benghazi Defence Brigades, originally from Benghazi and now occupying the central towns of Houn and Waddan, launched an offensive on 9 February against the Libyan National Army (LNA), which has since September controlled the Sirte Basin, the prolific heartland of Libya's oil sector.

The attack was beaten back before it got underway by a wave of LNA air and helicopter strikes. The forces, under the control of eastern general Khalifa Haftar, claimed to have destroyed 40 vehicles, but lost a helicopter in the process. The LNA also repulsed an attack late 2016.

Despite Libya's worsening civil war, oil production stands at more than 0.7m barrels a day, its highest level in nearly three years. Output capacity before the revolution against Muammar Qadhafi in 2011 was 1.6m b/d. National Oil Corporation (NOC) has talked of raising production to 1.2m b/d in 2017.

Recent output gains have been possible because of Haftar's capture of four oil ports serving the Sirte Basin. The LNA afterwards handed the terminals, and infrastructure connecting them to the basin's fields, to the NOC.

But the conflict is deepening and renewed targeting of energy installations cannot be ruled out. As well as battling Islamist forces at Houn and Waddan, Haftar's Operation Dignity, a coalition of LNA and tribal militias allied with the Tobruk-based House of Representatives (HoR), continues to fight against Libya Dawn, an Islamist-Misratan coalition whose militias also hold Tripoli.

Libya Dawn politicians form a majority in the UN-appointed Government of National Accord (GNA) in Tripoli. Two pro-Tobruk members of the GNA's nine-strong presidency continue to boycott the unity government, and a third has resigned, disrupting what the UN once hoped would be a finely balanced presidency representing all Libya's factions.

Tobruk's HoR refuses to recognise the GNA and has its own interim government. That has created a political paradox at the heart of Libya's chaos. While Tobruk-allied forces control the territory accounting for two-thirds of the country's oil, the GNA, by international resolutions of UN Security Council recognition, is the body authorised to sell it and disburse the proceeds.

"The LNA has its hands on the taps," said Mustafa Sanallah, chairman of NOC, recently. "And the GNA has [UN Security Council resolutions] 2259 and 2278. Each side has one key to the treasure room, but both keys are needed to open the door."

IOC exodus

Mustafa Sanallah-the chairman of the Libyan National Oil Corporation (NOC)-has made it his mission to open that door, insisting he is above politics, and holding a blizzard of meetings to persuade foreign firms to return to a country most fled when civil war erupted in 2014. He has also pled that the GNA's leadership release funds back to NOC to pay for much-needed remedial work on damaged energy infrastructure.

In January, Sanallah was in London to meet partners of Waha Oil Company, an NOC joint venture with US firms ConocoPhillips, Hess, and Marathon Oil, which has restored 50,000 b/d of its original 350,000 b/d production at five Sirte Basin fields.

Days later he held talks with Spain's Repsol, an NOC partner in the key southwestern Sharara field and Germany's Wintershall, which is producing 35,000 b/d from its Sirte Basin fields.

Sharara and the nearby El Feel field, operated by an NOC-Eni joint venture, are now able to begin exporting oil to terminals west of Tripoli, after militias blocking the fields agreed to their restart. Sharara's output has reached about 170,000 b/d, or around half its 2011 capacity. El Feel has yet to begin pumping.

But many foreign firms remain nervous. Tanker operators remain gun-shy and their insurers are demanding large premiums to cover the risk. On 13 February 2017, two days after NOC publicised the first shipment by subsidiary Mellitah Oil and Gas from a new vessel above the offshore Bouri field, Tripoli's most powerful pro-GNA militia, Rada, arrested several executives from Mellitah, a joint venture with Eni.

"Tanker operators are going to be wary due to previous oil threats," said Lisa Ward, co-founder of TankerTrackers.com, a new open-data surveyor of oil shipments. "In previous situations tankers have been prevented from loadings due to local power struggles."

The GNA, in Tripoli only with the approval of militias that control the capital, is also wobbling. It has been unable to establish its authority beyond the capital and Hafter's ascendency on the ground is bringing a shift in the diplomatic stance of Western powers.

Libya's Islamist and Misratan militias also now fear the loss of US support, despite having allied with American forces to oust Islamic State from Sirte. This has prompted some of them to form a new group, the National Guard, supporting yet another rival government, the National Salvation Government. Street battles in Tripoli between these factions have only escalated.

It all makes hopes for a swift end to Libya's political dysfunction - and a return of energy firms to help it sustain the oil-output recovery - look distant. "Oil companies are still in the wait-and-see mode," says Geoff Porter, president of North Africa Risk Consulting. "Security costs in Libya are, rightly or wrongly, sky-high. If oil companies can generate revenue more cheaply elsewhere, that's where they'll go."

ONES TO WATCH

Libya: fighting ongoing around Ras Lanuf and es-Sider oil terminals in Libya

Sectors: energy; banking; finance

Key Risks: airstrikes; terrorism; clashes

In Libya, fighting is expected to continue around the Ras Lanuf and es-Sider oil terminals and further east at Marsa Brega after the Benghazi Defence Brigades (SDB) attacked Libyan National Army (LNA) positions in the terminals on 3 March 2017. The LNA took control of the ports in September 2016 from the Petroleum Facilities Guard (PFG), which has carried out attacks with the SDB in the past. Further airstrikes by the LNA are likely after strikes on 4 and 5 March 2017 proved unsuccessful. The internationally-recognised National Oil Company (NOC) in Tripoli was due to meet to review loading schedules after es-Sider was evacuated due to the imminent takeover of the facility by SDB forces on 4 March 2017. The infrastructure of two of Libya’s largest oil terminals is at risk. The events may impact oil market sentiment and will have repercussions on Libyan domestic politics.

Islamic militias widen their influence, endangering production

Libyan Islamist militias have extended their control over two key central oil ports they seized on 3 March 2017, as the country's civil war escalates and threatens recent oil-output gains. A counter attack or full-blown war in Libya's oil-producing heartland may be imminent.

The militias, led by the Benghazi Defence Brigades (BDB), captured areas surrounding Es-Sider, Libya's largest export terminal, and nearby Ras Lanuf, a refinery and export complex, in a lightening attack on 3 March 2017, advancing against desultory air strikes across 270km of desert.

Their attack has tilted the balance in Libya's civil war, which had been with eastern strongman Khalifa Haftar, whose Libyan National Army (LNA) seized the two ports, along with nearby terminals Brega and Zueitin in September 2016.

The four facilities export oil from the prolific Sirte basin, home to two-thirds of Libyan output.

The National Oil Corporation (NOC), holding company for Libya's state oil assets, said Ras Lanuf and Es-Sider had now shut. Shipping sources said the first cancellation would affect loadings from 7 March 2017, when a tanker was scheduled to lift 0.63m barrels from Es-Sider.

NOC sources said production that had reached 0.7m barrels a day in February had fallen to 0.65m b/d as a result of the disruption. It is likely to drop more steeply.

Waha, a partnership between NOC, ConocoPhillips, Marathon Oil and Hess—and the largest of the Sirte basin's joint ventures—has cut production from 75,000 b/d to 40,000 b/d as a precautionary measure. Germany's Wintershall said it was maintaining production of 35,000 b/d from its C 96 field in central Sirte Basin.

It is unclear whether the militias have entered the ports themselves. One NOC source said local site managers insist the fighters have confined themselves to residential areas outside the perimeters, leaving port facilities untouched.

LNA units fell back over the weekend to Brega, with commanders saying they were massing for an impending counter-attack while daily air strikes have been launched against the militias.

The BDB is so named because its fighters hail from Benghazi. But they fled the city last year after the LNA captured much of it. In recent weeks, they had taken control of Wadda and Houn, from where they launched their assault on the terminals. The attack has also drawn support from Al Qaeda-linked fighters, according to the LNA.

At a press conference in Misrata, Benghazi militias leader Colonel Mustafa Alsharksi said his aim was to return the two ports to the control of the UN-appointed Government of National Accord, the rival administration the Tobruk-based parliament, which is allied with the LNA.

"Our main goal is to reject and say no to oppression, say no to military rule," Alsharksi said, a pointed reference to Haftar's growing authority in eastern Libya.

Alsharksi's choice of Misrata as the location for his press conference was a blunt indication of the prospect of a widening war. Misrata is the largest militia in Libya Dawn, a militia coalition that holds Tripoli and much of western Libya and is at war with the LNA

Appeal for calm

The LNA warned Misrata units on Monday 6 March 2017 not to drive east to reinforce the Benghazi militias, staging air strikes around the ports and at the towns of Ben Jawad, Harawa and Nawfiliya along the coastal highway west of Es-Sider.

The same day an appeal for calm was issued by the US, France and UK, with a joint statement backing the NOC and the UN accord. "We reaffirm the need to keep oil infrastructure, production, and export under the exclusive control of the NOC acting under the authority of the Government of National Accord (GNA)."

The GNA insisted it had no part in planning the attack. While Libya's civil war is notionally between the government in Tripoli and the parliament in Tobruk, in practice, it is the warlords who call the shots.

Parliament promoted Haftar to Field Marshall for his September's 2016 oil ports seizure, but he, not the politicians, runs the LNA.

Likewise, the GNA has no forces of its own, with its six-strong presidency mostly confined to a Tripoli naval base while Libya Dawn militias are fighting among themselves, some supporting the GNA, some a third rival administration, the Salvation Government. While the fight for the port was underway on 3 March 2017, pro-Salvation Government units stormed the NOC's Tripoli headquarters, issuing a TV broadcast claiming they now controlled the corporation.

NOC's chairman, Mustafa Sanallah, denounced the continuing militia occupation of his headquarters, saying 6 March 2017: "I strongly condemn cheap tricks like this that try to drag NOC into politics. Above all, NOC and the oil sector should not be a bargaining chip in the political conflict."

Haftar's capture of the oil ports last September saw production jump from less than 300,000 b/d to 0.7m b/d in February, half the 1.4 million b/d figure before civil war broke out in July 2014.

This revival saw NOC issue bullish predictions about future growth. On 24 January 2017, Sanallah predicted production would hit 1.25m b/d by year's end. On 22 February, he signed of an outline production and exploration deal with Russian state oil giant Rosneft in London. He also said output would rise to 2.1m b/d by 2022.

But these plans—like current output levels—are threatened by the escalating civil war. "The five-month period of relative cohesion when it comes to Libya's oil output was, in fact, a bit too good to be true," said financial analyst Jalel Harchaoui, a researcher covering Libya at France's Université de Paris 8. "Since February 2017, a lot of folks on both sides of Libya's fault line were getting agitated. The various factions adopted a more aggressive discourse with regards to the oil."