Energy Security Intelligence Research

ESIR

ESG STRATEGY RISK and COMPLIANCE PLANNING AGENDA 2050

OPEC Countries

We

share our collective knowledge of the oil and gas market, production and exploration, oil spot price, impacts on markets, benchmark contract delivery price and expertise by offering

a range of complementary

service—either as

part of a client-wide strategy or

customized to suit individual requirement:

our best knowledge-based

resources at your disposal.

We provide OPEC update, oil and gas market, West Texas Intermediate (WTI) and Brent price, oil field post-tax breakeven (Fiscal Terms); force mageure in upstream and downstream sector, proposed and on-going projects, political and economic risk assessment; and new financing risk in oil and gas industry.

"In ESIR, we are always looking to the future. As trading oil and gas businesses move from their historic position as providers of liquidity and logistical expertise to the market towards being owners and operators of strategic assets in which National Oil Companies (IOCs) have a strong interest, they are likely to find themselves facing new-and possibly exacting technological diffusion challenges"

A Reputation for Excellence

“To succeed, you need advisers who understand the environment in which you operate. We have people who have worked in energy industry, people who have a track record of advising on services providers, country legal structure, funding and assets restructuring in the era of low oil price”

Click on the individual country below for consultancy advise, research insights and data analysis.

Adding Value through Distribution and Logistics.

"The desire to secure the route to market and capture additional market share from the downstream supply chain is the second component of the trend towards economic stability in resource dependent countries. Depending on the industry, but in oil and gas trading, this can take a number of forms: building the transportation infrastructure required to access new supplies; expanding into the transportation or shipping sectors; or acquiring control of storage facilities waiting for upward price swing"

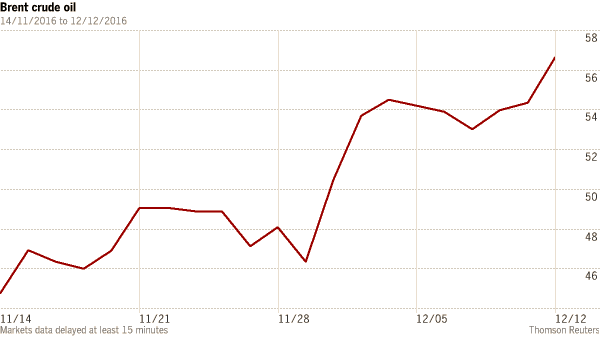

Oil prices surge to highest level since July 2015

Market welcomes supply agreement from non-OPEC producers

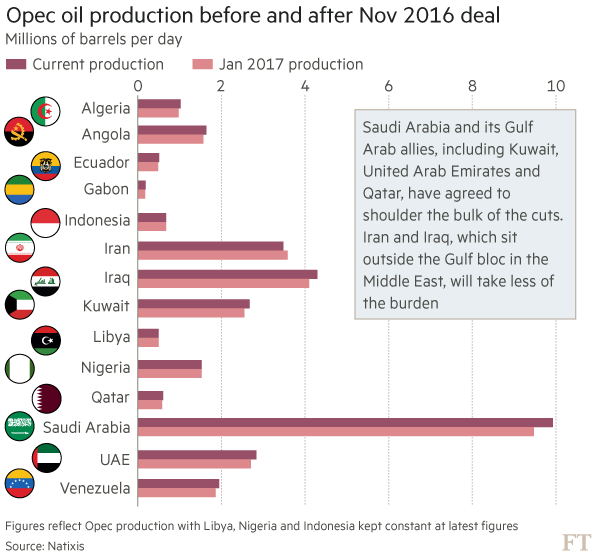

Energy Markets welcome Oil prices surged above $57 a barrel for the first time since July 2015 on Monday December 12, 2016 rallying as much as 6.5 per cent after the OPEC cartel clinched a long-sought supply pact with Russia and other big crude exporters. Russia led a loose coalition oil producers from outside OPEC, including Oman, Mexico and Kazakhstan, in an agreement signed in November 2016 to reduce supply by 558,000 barrels a day — with Moscow agreeing to shoulder just over half the cut. Saudi Arabia, the most powerful member in OPEC, said it may now cut supply further than it initially pledged when OPEC’s 13 members agreed their own supply cut of more than 1m barrels a day on November 30, 2016.The deals amount to the first global supply pact since 2001, with producers battling to reverse a two-year price crash that has cut deeply into their revenues, slashed industry spending worldwide, and left many oil-dependent economies mired in recession. “Non-OPEC participation should add to bullish sentiment . . . [and] continue to support the oil rally into 2017,” said Morgan Stanley analyst Adam Longson. Brent, the international oil benchmark, jumped by more than $3 a barrel minutes after the open in Asia on Monday December 12, 2016 to hit a year-high of $57.89, with traders scrambling to buy back bets placed against the price, before paring gains slightly. It has risen more than 20 per cent since OPEC’s initial deal less than two weeks ago. International energy companies have been boosted by the crude rally, with share prices for BP and Royal Dutch Shell both up more than 10 per cent this month, while US shale-focused companies like Continental Resources and Anadarko Petroleum have risen more than 15 per cent. Traders are likely to shift focus to the implementation of the deal, with concerns some of the supply cuts may not materialise or consist of generous interpretations, including natural decline rates at mature fields in some non-OPEC countries. But the backing for the deal from the Russian president, Vladimir Putin, and Saudi Arabia’s royal family should make traders take the deal seriously, analysts said, with the need for a higher oil price forcing the two countries to overcome animosity stoked over their support for opposing sides in Syria’s bloody civil war.

However, Some justifiable doubts will remain over the implementation of the production quotas which have been announced, said analysts at JBC Energy in Vienna. But the ability of Saudi Arabia and Russia to come to an agreement in the current climate has to be seen as a significant statement of intent. The push to retake control of oil supply by Saudi Arabia has reversed its earlier decision to open the spigots to try to squeeze out other high-cost producers. US shale, in particular, will be watched closely to see if a sustained recovery in price can reignite an industry that was always the most visible target of OPEC’s market share battle, given its rapid growth between 2011 and 2015. That may prove the biggest threat to the price recovery. While US oil production has fallen by about 10 per cent since prices crashed from an average of more than $100 a barrel in the preceding four years, suppliers have cut costs and refinanced. Last week (first week of December 2016) US oil drillers added more rigs than at any time since July 2015, according to energy service company Baker Hughes. OPEC members Nigeria and Libya, whose production has been hit by violence, may also see higher output in the coming months. “OPEC have taken a very important step towards stopping the relentless build up in global [oil inventory] stock levels,” said David Hufton at oil brokerage PVM.“As long as compliance is strong, Libya and Nigeria fail to rebound and US producers take time to respond.”

The oil glut will linger, despite Opec's best efforts

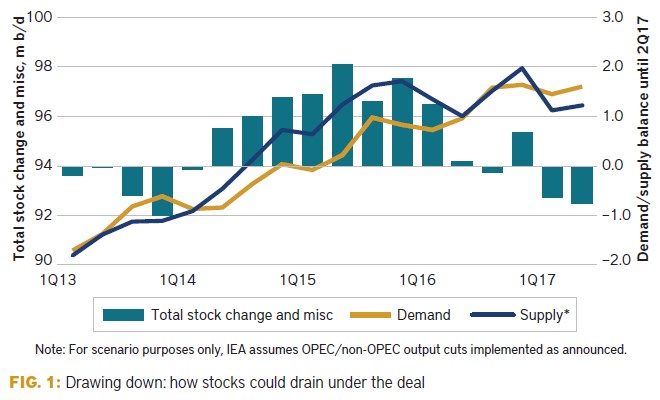

Price stability, at a higher level, is what the cuts are designed to achieve. But to bring that about Opec needs to drain a glut of crude that has built up over the past few years. Khalid al-Falih, Saudi Arabia's oil minister, says he thinks the market will be balanced by mid-2017. Others aren't so sure.

It certainly looks like it will take longer than half a year to tame the raging overhang. If so, whatever Falih says, Opec will probably need to extend its deal in May for the rest of 2017.

"Riyadh knows that running down the overhang will take longer than six months, and one year is widely seen as the time needed to rebalance the market," wrote Amrita Sen, head of consultancy Energy Aspects, in a recent note. "Moreover, stock draws will also push the curve into backwardation-although not until late this year given the size of the overhang-which will deter producers, particularly those in the US, from hedging further forward, a positive for Opec members."

The pace of any draw will depend on whether producers implement their cuts as promised, as well as the level of oil demand over the coming months. Neither is easy to forecast. But the International Energy Agency (IEA) says OECD stocks presently stand at 3.033bn barrels, or 311m barrels above their five-year average-so Opec certainly has its work cut out.

The agreement calls for Opec members to reduce production by 1.16m barrels a day over the first half of 2017, bringing output down to 32.5m b/d. Non-Opec members, including Russia, Mexico and Azerbaijan, have pledged a further 0.558m b/d of cuts, bringing the total to around 1.8m b/d.

Aside from watching how many of these barrels of oil aren't produced, the market will be keenly focused on Libya and Nigeria-both exempt from the cuts, but capable of adding much more output in the coming months. Also, the cut deal is for production, not exports. Some countries, like Russia, may keep their supply to the market robust, even while wellhead extraction falls.

The IEA said in December that if Opec "promptly and fully" stuck to its production target and non-Opec delivered as pledged, the market would move into deficit in the first half of 2017. In January, it said the Opec deal-if complied with-would imply a draw of 0.7m b/d.

In mid-January, Opec's secretary-general, Mohammad Barkindo, said he expected global oil inventories to fall by the second quarter of this year in response to the cuts.

But one thorny issue is identifying how big the supply overhang actually is. Despite the bold predictions, no one could truthfully claim to know the precise figure. While data on oil storage from the US, Japan and Europe are fairly transparent, pinning down stored volumes in other areas can be more problematic. Separating out crude oil and products stocks is also tricky.

Alan Gelder, an oil-markets analyst at consultancy Wood Mackenzie, expects the overhang will still be in place by the year's end. That's based on the assumption that the agreement lasts only for six months and Opec countries muster cuts of around 1m b/d (compliance of about 80%), while Russia cuts around 200,000 b/d, or two-thirds of its pledge. This would pull 100m barrels from inventories by end-2017, he says. It would be enough to support an oil price of $60 a barrel. A 100% compliance would end the overhang in the second half of the year and push prices to $70/b-at which point US tight oil supply would surge.

Sen believes compliance of around 80% is feasible. Gulf Cooperation Council states, accounting for 0.8m b/d of the cuts, can be counted on to deliver. Iraq, on the hook for 210,000 b/d of cuts, is less certain. Few observers expect it to stick to its pledge-not least because the government in Baghdad cannot control exports from the Kurdish-controlled north. Alongside potential growth from Nigeria and Libya, such slippage would slow the glut's clearing.

On the other hand, Saudi Arabia has hinted that it may cut deeper than the 486,000 b/d it agreed to. Angola claims already to have fully complied with its 78,000 b/d reduction (but also has plans to increase capacity). Crisis-hit Venezuela may end up involuntarily losing much more supply than it agreed to remove.

Opec's own market outlook foresees a much swifter draining of the swamp. It calculates that non-Opec supply fell by 0.71m b/d, to 57.14m b/d, in 2016 and expects just 120,000 b/d of growth in 2017. That's a crucial number, because unlike Opec producers now scrambling to live up to their deal, non-Opec producers-especially smaller tight oil ones-are under pressure from banks and other lenders to keep cash flow ticking along. Many of them have been able to hedge prices, thanks to the rally following the Opec deal. So it's possible Opec is underestimating how much supply they'll add in the coming months.

That's the group's main dilemma. It wants higher oil prices-and so needs the market to start pulling crude from global stockpiles. But, in doing its best to make this happen, Opec risks pushing prices to a level that will revive other suppliers, dampen demand growth and maybe even tempt some of its own members to pump more than they agreed.

OPEC's narrowing options: An extension to the cuts may not help the group as much as it helps North America Shale Producers

OPEC meets this week (25 May 2017) in Vienna and for all the back-slapping about record-high compliance with its cuts, things are not going in the group's favour. Opening the taps, as it did in late 2014, brings weak prices and intolerable fiscal pain. Tightening supply, as it has done since January, can stop another price collapse but in reality it just subsidises American shale. For now, OPEC is sticking with the second of the two bad options. Texas will be pleased.

Surprises are unlikely at the meeting on 25 May. All OPEC's signals to the market have been to expect a rollover of the cuts, possibly for another nine months (instead of six) or even a full year. Venezuela, as ever, would like everyone to slash more supply, but that seems unlikely. Although Saudi Arabia's oil minister Khalid al-Falih has said he will do "whatever it takes" to help bring balance back to global supply and demand, the kingdom doesn't want to shoulder yet more of the burden, especially when its rivals Iran and Iraq remain such ambivalent cutters. A rollover is the best outcome. The meeting in Vienna might be mercifully brief—some members of the Saudi delegation, including the minister for energy affairs, prince Abdulaziz, are said to not even be attending.

The outcome and the communiqué will matter to the oil market, of course, but price direction for the rest of this year will be set elsewhere—in Texas, on Wall Street, in North and West Africa, and by the world's fickle consumers.

OPEC's main achievement after six months has been to prevent another collapse in the price. Global demand was weaker than expected in the first quarter, so keeping Brent around $50 a barrel took some doing. Compliance with the cuts was high—96%, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). The non-OPEC cutters did less well, removing more than half (369,000 barrels a day) of the 0.558m b/d pledged. Russia promised 300,000 b/d but had cut just 231,000 b/d by April. It will endorse the extension.

What the cuts have not done, yet, is drain a global surfeit of stocks. The much-touted rebalancing of the market—OPEC has said repeatedly in the past two years that it is nearing—remains ever distant. The group's narrative until recent weeks was about another heave in the cuts to bring balance by end-2017. Now the willingness to extend the cuts into 2018 suggests another delay. No wonder: Falih wants OECD oil inventories to fall back to the five-year average but in March the surplus remained 276m barrels above that target. The IEA says stocks might have risen again in April.

Swinging shale

What the cuts have done, though, is nourish America's oil patch—and far more quickly than OPEC expected. The modest price gains the group's cuts engineered this year have restored cash flow for these drillers, revived moribund firms and allowed canny ones to hedge production. Wall Street has opened its purse again. And provided OPEC keeps sacrificing some of its oil supply to buoy America's, shale output could deaden the impact of the cuts—on the price and on stock levels.

The scale of the American recovery will shock OPEC again. Although it raised its forecast for tight oil growth this year (to 0.614m b/d), the group is still probably undershooting. Between April and May 2017, the main shale basins in the US added 124,000 b/d , a huge leap in just one month. Since October last year—when news of OPEC's plan to cut helped spark more activity—American producers have lifted output by 0.8m b/d. A recent analysis by the CME Group calculated that the 174 rigs added in the US over the past four months "could easily add" another 0.6m b/d of production by the end of Q3.

And OPEC's own non-cutting members are also making hay. Libya has increased its production by almost 400,000 b/d in the past six weeks. Nigeria's rose by 80,000 b/d in April, but the longer the truce lasts in the Niger Delta the better its chances of restoring up to 0.6m b/d of lost output capacity. Vessels are loading crude from the Forcados terminal, the resumption of which should on its own increase Nigerian exports by 200,000 b/d.

If the extra supply potential this year isn't enough to undermine OPECs efforts, demand might. The IEA still expects 1.3m b/d of growth this year—a baseline outlook used by countless analytical models to show when OECD stocks might return to normal levels. But the weakness in Q1 is troubling. Growth for that quarter was just 1m b/d year-on-year. For the whole year to reach the 1.3m b/d annual increase means the Q1-Q4 rise will be 2.6m b/d, says the agency. But in the past few years the average has been just 2m b/d.

This bearish scenario—tight oil plus Libya plus Nigeria plus tepid demand—isn't inevitable. A strong driving season in the US would perk up the outlook, for example, and much refining capacity should come back on line soon to soak up some of the supply excess. But OPEC's problem these days is that too many factors are beyond its control, starting with those resilient Texan drillers. In an era when Baker Hughes can snuff out a rally by updating its rig-count spreadsheet, the market force is not with OPEC.

Can OPEC get its swing production leverage back in St Petersburg?

Ecuador is too small to be a deal-breaker for OPEC. But when its oil minister Carlos Perez announced on 18 July 2017 that, needing cash, his country would sling its production quota and start lifting output again, it summed up OPEC's problem.

When prices rise to compensate for output cuts, great. But Brent, at around $49 a barrel on 19 July 2017, is 9% beneath its level when OPEC extended its deal at the end of May 2017. If you think prices aren't going to move much higher soon, then it's rational to pump more while you can.

Other members itch to do the same. Iran and Iraq both strain at the leash. They and Angola both upped their output marginally in June. Saudi production also rose, though remains in line with its quota. The International Energy Agency calculates that compliance dropped to 78% in June compared with 98% in May. When Libyan, Nigerian and new member Equatorial Guinea's production are rolled in, pricing agency Platts reckons OPEC was producing 0.6m b/d above its ceiling in June 2017.

The surprise is that OPEC's compliance remained so high for so long. Past deals started to fall apart much more quickly. Looking back to events, in January 2009, just a month after OPEC had agreed further cuts in Algeria, production was already 1.8m b/d above the target. After 12 months, compliance was just 58%. At least Ecuador had the grace to announce its intent to ditch the deal publicly.

Saudi Arabia, still convinced that the cuts will do their job in clearing the OECD stock overhang by the end of Q1 2018, is now trying to persuade others to hold fast. It contacted Ecuador (which reiterated its commitment to help clear the inventory—but didn't change its mind) and Nigeria (which is under pressure to agree a cap on its production growth) and has discussed other measures to keep the deal credible.

Russia, which plays host to OPEC's Joint Ministerial Monitoring Committee in St Petersburg on 24 July 2017, is lurking in the background. Its cooperation with OPEC was predicated on the group delivering its side of the bargain. OPEC did. But Russia's producers—which also want to increase output—will watch the compliance drop with a keen eye. The kingdom knows that if Russia reneges then the agreement collapses. Prices would plummet.

For OPEC, that might be the most logical move: let the deal wither and allow prices to do the job of rationalising (non-OPEC) supply. This is a popular idea among some in the Gulf, especially in Qatar. But a return to Naimism and the production free-for-all that followed the November 2014 OPEC meeting is not being considered in Riyadh (yet). Plan A still sees the market rebalancing over the next three quarters.

Yet to keep Moscow interested, Riyadh must do something to perk up the market. The first port of call in the past 18 months has been aggressive language (like oil minister Khalid al-Falih's pledge to "do whatever it takes"). But the market has tired of the jawboning. A deeper cut in exports is reportedly under consideration—most likely to be achieved by not lifting production during the peak domestic summer crude-burn season. The premise is that OPEC must account for the rise in Libyan and Nigerian supply in recent months. Saudi Arabia is the only producer with the will or means to make room for that oil.

Another move would include some risk. The market would welcome real signs that supply (exports) and not just production was coming down. But any price rise would motivate drillers in the US, threatening the rally. A drop in Saudi supply would also remove heavy barrels—but the glut is of light oil.

Still, if managed carefully—including a firm pledge to stick with the end-Q1 deadline for the cuts—trimming exports now would tighten balances through the rest of 2017 but build expectations of an OPEC supply onslaught in Q2 2018. In theory, this should induce backwardation in the forward curve. OPEC needs that, because otherwise tight oil producers can keep banking on higher prices next year.

If it is to act, OPEC should do it quickly, probably explaining the new policy tweak in St Petersburg next week. As Ecuador's decision shows, the cutters need a reason to keep cutting and stick with the plan; either signs of price recovery or evidence the deal is doing more than just subsidising non-OPEC's production revival.

Gulf members try to shore up OPEC's credibility

But a pathway out of the cuts is still not clear

OPEC's big guns are pulling out the stops. It should do the trick, tightening physical supplies and inflating the price this quarter, at least until refining maintenance kicks in again. But the big question remains: what is the end game?

For now, the policy is reactive, not proactive. OPEC needed to do something and has.

The backdrop to its latest meeting in St Petersburg earlier this week wasn't pretty. Compliance with the cuts has started to creak. Brent, at around $48 a barrel on the eve of the summit, had fallen by more than 10% since OPEC and its non-OPEC partners agreed in May 2017 to extend their deal. Market sentiment in recent months has been deeply bearish.

Bigger problems have been building. Russia, it is understood, was unhappy that the production recovery in Libya and Nigeria had neutralised much of the cuts' impact. Its implicit threat was that OPEC needed to put its house in order—or it might walk. Reports surfaced that, under pressure from Moscow, Riyadh would consider trimming more supply.

So it will. Saudi exports will fall to 6.6m barrels a day in August 2017. Sceptics will say the new cuts reflect only the domestic crude-burning season in the kingdom, and would have happened anyway. But as far as tweaks to the existing deal go, this is a big deal, whichever way you dice it. The last time the kingdom's exports were as low was in May 2011. It breaks what was said to be a redline minimum of 7m b/d of exports. It's a drop of about 0.5m b/d compared with its average for the year up until May 2017; and 0.7m b/d less than in August 2016.

Adding force, the UAE will cut supply by 10% in September 2017—its oil minister tweeted the news and said his customers had been told. On 26 July 2017, Kuwait reportedly jumped aboard too, pledging to cut its supplies as well.

The announcements since Petersburg have been worth a couple of dollars on the price. But a rally can only go so far. Significant inflation above $50/b would bring too much verve in the tight oil sector—just when it is starting to wobble again. But if the Gulf producers come good on their pledge then about 1m b/d of supply that would have reached the market won't.

Yet the latest tactical trimming can't mask some of OPEC's other problems. First, Russia's hold over the group is now plain—quite an achievement for a non-member. It has cut less than half the volume Saudi Arabia has removed, but is still able to influence policy.

Second, as ever Saudi Arabia and its Gulf allies are left to do the heavy lifting. Tiny Ecuador's decision to stop cutting won't cause these countries much distress. But Iraq, which has already said it will pump more this year and has been a compliance laggard, will. It's hard to see how Baghdad can be strong-armed into sticking with the cuts if it decides they've run their course.

Lastly, OPEC still has to figure out a way to end the cuts. It hopes that demand growth and the past two years' pull-back in upstream investment will yield a dearth of new production, leaving OPEC's oil riding to fill the void. But this can't be a reliable strategy. Time and again in recent years the market has surprised OPEC.

Indeed, expectations of a supply gap, according to energy analysts, are "the glue that keeps the OPEC deal together". But what if, as analysts predicts, this supply gap will not be "as big or as soon" as people thought? Other forecasters says, "still fail to grasp the size and economic viability of the US resource base".

Tight oil remains an oil-price-inflation killer: a reserve of economical oil able to snuff out rallies just when they gain momentum. If that means prices can't move much higher, OPEC's main task will be to make sure they don't drop much lower. And without an exit strategy, the group knows that terminating its cuts would just open up a wave of its own supply, undoing all the work to create a price floor.

What does the end look like? Is it when OECD stocks are at their five-year average? Is it at $55/b or $60/b? What happens to the inventory when OPEC stops cutting? What happens to prices? No one is sure, because OPEC, rife with members desperate for short-term relief, doesn't seem to be looking that far ahead.