Energy Security Intelligence Research

ESIR

ESG STRATEGY RISK and COMPLIANCE PLANNING AGENDA 2050

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Trading Margins in Energy Sector in the US is tightening. Why?

Large energy companies have always employed extensive intelligence-gathering operation to obtain the latest market information, for example counting competitors' exploration and production and their production margin to get a picture of oil and company's output of a particular field.

However, recent production techniques of oil and gas have seen a move towards the control of transportation and storage. In January 2012 for example, Gunvor-the Russian oil trader-bought a refinery which has a storage capacity of more than 1.2 million cbm strategically located in the Amsterdam-Rotterdam-Antewerp oil trading hub. Deals such as these not only offer a secure route to market, but a significant competitive advantage over rivals by virtue of superior information. They can also allow a trading company to impact its peers' trading patterns and profitability.

Moreover, since the oil and gas industry suffered a sharp drop in profitability in the second half of 2014 amid weaker global demand and trading margins are being squeezed and this continued into 2016. These pressures, combined with funding issues, are leading trading businesses to proactively look at new structures and business models including significant re-structuring as businesses seek either to merge for size or shrink for technological innovation.

For instance, BP warned investors that 2016 would be another "stressful year" and, in April 2016 reported a 56% decrease in earnings from continuing operations from a record USD 2.69 billion in the prior year to USD 1.5 billion.

In addition, trading oil and gas companies are likely to face a number of challenges of their own going forward:

- the shortage of funds from the banking sector is likely to remain a difficulty across all markets;

- the expansion of trading houses is likely to result in greater market concentration, which may in turn increase the regulatory burden on commodities firms, with the result that regulatory approvals and clearance from competition authorities will be required for their mergers and acquisitions.

Indeed, there is already concern amongst global policymakers that some trading houses might become "too big to fail". In a recent speech, Timothy Lane, deputy governor of the Bank of Canada, said that some of the large energy companies and the physical trading operations of some large investment banks are too exposed, and are "becoming systemically important".

US Oil and Gas Update

An onslaught of new supply from the US will continue to pressure LNG prices in 2017

US gas output tumbled in 2016. The Energy Information Administration (EIA) expected production from the country's seven most prolific regions to fall to 46.95bn cubic feet per day in December. That's down from almost 48.18bn cf/d in February. For all of 2016, the EIA expects total gas output to fall by 1.4bn cf/d, to 77.3bn cf/d. It may at last bring American gas supply's gravity-defying act to an end.

In fact, US natural gas production has been contracting since mid-2015-reflecting a decline in conventional production and shale oil-associated output. Associated gas production has dropped in most of the country's crude-rich plays over the past two years, including the Eagle Ford, Bakken and Niobrara areas.

But the EIA expected that gas production started rising again in November as rig numbers increased and infrastructure capacity connecting production with consumers came on line. These build-outs could boost output by as much as 2.9bn cf/d in 2017, the EIA said. While US gas rig numbers have begun to increase, according to Baker Hughes, at just 116 in November they remained around 40% below year-earlier levels. Some analysts are not as optimistic as the EIA. Bank of America Merrill Lynch expects average dry gas output to fall by around 0.6bn cf/d in 2017 before contracting by another 8bn cf/d in 2018.

Whether US gas output recovers next year or not, domestic demand is rising-so the market should tighten. The EIA expects US gas consumption to rise by around 370m cf/d, or 0.5%, in 2017, reaching 76.06bn cf/d. Investments in methanol and ammonia plants are boosting consumption, while liquefied natural gas exports are also pulling on supplies.

BAML expects demand for LNG exports will reach 2bn cf/d by the end of 2017. By 2018 demand for exports will more than double, to 5bn cf/d.

Even if domestic gas output increases in 2017 more LNG shipments and pipeline exports to Mexico should support Henry Hub prices. The EIA expects prices to average $3.12 per million British thermal units in 2017, up from around $2.50/m Btu in 2016. BAML see Henry Hub reaching around $3.50/m Btu and $3.30/m Btu in 2017. However, another 36.1m tonnes of new liquefied natural gas supply will be shipped in 2017 from US producers worsening the global supply glut. Total LNG exports will soar to 282.5m tonnes during the coming 12 months.

Liquefaction capacity additions in 2017 will rise even more steeply, growing by 51m tonnes a year to a total of 393m t/y. That comes on top of 39m t/y of capacity added in 2016. LNG shipments in Australia and Asia will reach 118m tonnes, a rise of 18%, or 21.3m tonnes, compared with 2016. Australia alone will add 26m t/y of new liquefaction capacity (to reach a total of 86m t/y), as new projects including Chevron's 8.9m-t/y wheatstone project come on line.

Demand won't keep pace. Emerging Asia will be the main locus of growth, helping the region's imports reach 186.6m tonnes. But falling demand from Japan and South Korea means overall consumption will rise by just 4.4m tonnes, or 3%.

The excess will find its way to Europe, where imports will surge by 36% from a year earlier, reaching 65.5m tonnes. Coal-to-gas switching in the power sector will soak up some of this. But prices will have to fall to accommodate this much supply.

EIA predict that average spot LNG prices will drop below $5 per million British thermal units in 2017 in key markets including Japan, India, Spain and Argentina. By 2018, they are expected to fall even further, to under $4/m Btu. Japanese and Indian buyers paid around $7.50/m Btu in 2015.

Only in the US are natural gas prices expected to rise. But US gas will still be cheap: EIA expects Henry Hub to average around $3.30/m Btu, up from around $2.60/m Btu in 2016.

Coal prices will be a wild card next year. Prices surged towards the end of 2016 owing to China's reduced production capacity. If the country relaxes constraints on coal mines-to limit the rise in imports and soften prices-Asian LNG imports will weaken.

What would the US border tax adjustment mean for energy?

From opening new areas for drilling to accelerated pipeline permitting to scrapping regulations, there is no lack of speculation about what Donald Trump's energy agenda will mean for oil and gas. But the most consequential policy change on the horizon is not an energy one at all—it's rather a major overhaul of the US corporate tax code.

Among the most controversial parts of the tax-reform package put forward by the House Republicans is the so-called border tax adjustment (BTA). This would effectively act as a charge on the US trade deficit by taxing imports and subsidising exports. Under the proposal, the corporate tax rate would be lowered from 35% to 20% or even 15%, and the US would replace the current system that taxes profits anywhere in the world when brought back to the US with a "destination-based cash-flow tax" (DBCFT) that would tax corporations based on where their products are used. To implement this system, the cash-flow tax would be paired with a BTA that would exclude both import costs and export revenues from a company's tax obligation.

For example, a US refiner that imports all its crude feedstock for $50 per barrel and sells refined products at home for $100/b (unrealistic, but simplified) will pay the 20% tax on the full $100 (that is, $20), not on the $50 "profit" (that is, $10) that would be the case without border adjustment. On the other hand, a US refiner buying all its crude from US producers for $50 and selling all its products abroad for $100 would have a loss of $50, pay no tax at all and might even get a refund (compared with a $10 tax without the border adjustment). This will look like protecting domestic industries through tax discrimination, and may fall foul of WTO's rule of level playing field in global trade competitiveness.

The principle behind the DBCFT is already familiar throughout the world with the use of value-added taxes (VATs), although there are important differences. Rather than applying the corporate tax where goods and services are produced, or where the company is headquartered, as the current corporate income tax does, the DBCFT imposes the tax in the jurisdiction where the goods are sold. To tax goods where they are sold, however, imports must be subject to the tax and exports exempt from the tax—hence the BTA.

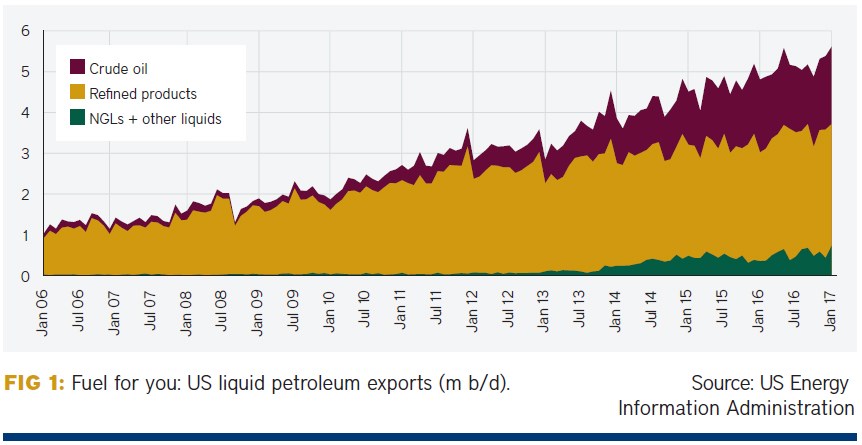

The impacts of a BTA on the oil patch are complex, especially given the recent increases in US production and shifts in the country's energy trade. Net petroleum imports have declined from 60% of US consumption a decade ago to just 25% last year. Nonetheless, the US remains a massive net importer of petroleum. These net figures also mask a large and growing dependence on petroleum trade. While the US imports 7.1m barrels per day of crude oil on net, the gross figure is 7.6m b/d, because about 0.5m b/d is exported at the same time. Given the configuration of American refineries, the US imports much heavy crude and increasingly exports light tight oil. In February 2017, crude exports rose sharply, peaking at 1.2m b/d, as refineries went offline for maintenance and supplies tightened in Asia following the Opec cuts. Trade in refined petroleum products is even more pronounced. Over the past decade, the US has gone from the world's largest importer of refined products to its largest exporter. And the US this year joined the ranks of net natural gas exporters. Within a few years it will be one of the world's largest gas exporters.

At first glance, it would seem from the example above that US exporters win and importers lose. But the effects are far more complex. The adverse effects on the oil and gas sector could be much broader, as explained in a forthcoming in-depth study by Jason Bordoff and Akos Losz from the Columbia University Center on Global Energy Policy.

Dollar surge

While the impacts are varied, a key point to start with is that a BTA would likely have a depressive effect on world oil markets through the appreciation of the US dollar. Economists generally agree that by reducing demand for imported goods and boosting demand for exports, a BTA will cause the dollar to appreciate. That is because the increase in foreign demand for US products will increase foreign demand for US dollars, while the reduction in demand for less-competitive imports will reduce the supply of dollars to foreign holders.

Yet there is much disagreement about the extent and timing of the dollar adjustment. While many economists that specialise in tax issues think the currency adjustment will happen immediately and completely, many others—especially ones who focus more on exchange rate markets—believe it will take time and happen only partially at best.

If the US dollar increases due to a US-specific shock like a tax-policy change, then global markets should—theoretically—adjust to keep the global price of dollar-denominated oil in other currencies constant. So that would suggest that the dollar price of oil should fall by one-to-one to offset the rise in the dollar. That is because a US-specific shock should not have implications for the equilibrium price of oil relative to other goods and services in the rest of the world. If the dollar has appreciated, the only way in which oil (priced in domestic currency) can maintain its relative price with other goods and services is for the oil price to fall. While a shock to the dollar value would typically suggest other dynamics in and implications for the global economy and oil market, a domestic tax change in the US is a good proxy for an exogenous, US-specific shock that minimises these other impacts.

Therefore, "BTA would likely have a depressive effect on world oil markets through the appreciation of the US dollar".

However, to be sure, this is a textbook description. In reality, exchange and commodity markets may not work in such a perfect way. To the extent world oil prices do not fall to fully offset the rise in the US dollar, then, since oil is a dollar-denominated commodity, oil will become more expensive in local currencies, leading to higher pump prices, which would reduce demand, also putting downward pressure on prices.

Yet while a BTA would depress world oil prices through dollar appreciation, it would likely push up oil prices in the US, creating a wedge between the two. To understand why, consider how a domestic oil producer would respond to a BTA in a stylised example (ignoring transportation cost differentials) that assumes a 20% corporate tax rate and a $50/b oil price. The domestic producer has two options. It can sell a barrel of oil to a domestic buyer (like a refiner), in which case it will pay 20% tax on the $50 it receives. Or it can export the barrel and pay no tax on the $50 it receives. For the domestic producer to be indifferent between selling the oil domestically and selling the oil to a foreign buyer—for it to receive the same $50 for the barrel—the domestic producer would need to receive $62.50/b to sell oil domestically, or 25% more than the prevailing world oil price.

Benchmark flux

The extent to which the US oil price rises and world oil price falls depends on the degree to which the dollar appreciates. If WTI and Brent were both $50/b before BTA adoption, and the dollar appreciation were full and immediate to offset the BTA, the world oil price would likely fall to $40, leaving the US oil price unchanged. If the dollar did not appreciate at all, WTI would rise to $62.50 and Brent would remain at $50 (ignoring, for now, other dynamic effects like the US supply response to higher WTI). In reality, the most likely outcome is somewhere in between, with partial dollar adjustment. So WTI would be higher, Brent would be lower, and both may be gradually dragged down during the period of dollar appreciation.

The impact on oil prices will also be affected by the impact of a rise in domestic oil prices on US supply—which, importantly, is far different today than it was just a decade ago because of the shale revolution. In the past, a policy that pushed up domestic oil prices would have largely resulted in rents to producers. Today, a bump in the price of oil, of say $10/b, may mean higher US production of anywhere from 0.4m to 0.8m b/d. That extra supply will partially offset the higher pump prices potentially faced by US consumers as a result of a higher WTI price. And it would likely further depress world oil prices beyond the impact of dollar appreciation.

A stronger dollar may also help prop up global output by reducing production costs in local currencies around the world, further pressuring world prices. Recent trends in Russian production, for example, illustrate how weakening local currencies can more than counter headwinds from global oversupply and low oil prices. Producers in many other countries, such as Colombia, Canada, Norway, Venezuela and the UK, also pay for most upstream costs in local currency.

The extent of any world oil-price decline may be offset if Opec were to cut output yet further to prop up prices. In practice, it seems unlikely the group would respond in this way. Even absent a BTA, US shale oil production is poised to surge this year as prices recover, which may challenge compliance with the existing Opec agreement if producers feel like their market share is just being replaced by supply from the US and other producers like Canada and Brazil. Both the Saudi and Russian energy ministers pledged their commitment to the deal at CERAWeek in March 2017, but there is surely a limit to how much burden they will bear if inventories are not drawing down quickly enough and further cuts are required in response to even stronger US shale growth. Saudi oil minister Khalid al-Falih has been clear that the kingdom will not shoulder the burden alone if compliance by other Opec and non-Opec members begins to falter.

Geopolitical impact

Lower oil prices and a stronger dollar will have geopolitical consequences. As the recent price collapse made all too clear, from Venezuela and Nigeria to Iraq and Saudi Arabia, low prices can upend existing geopolitical relationships, foster instability in key regions, and present new geopolitical risks. A stronger dollar means that foreign holders of dollar-denominated debt could see their debt obligations rise, and weaker relative currencies might slow growth in emerging markets. A stronger US dollar would also strain economies that peg their currency to the dollar—notably Saudi Arabia, already feeling the pain of low prices as it implements an ambitious economic reform agenda. (If the dollar were to appreciate without depressing oil prices, of course, the Saudis would stand to benefit from a positive terms-of-trade shock, as their oil revenue in dollars would be worth more relative to other currencies.) A fall in demand and prices may also push down the local currencies of oil exporters with floating currencies, for example the ruble in Russia.

The impacts on corporate oil producers would vary. In some ways, they would benefit. For example, US producers, especially independents, would benefit from being able to fetch higher prices for their crude. They may also benefit from a lower corporate income tax rate, depending on their tax liability. And producers outside the US would be helped by lower supply-chain costs to the extent these are priced in a depreciated local currency.

Refiners may be harmed by having to pay more for their crude inputs to turn into gasoline, diesel and other products.

On the other hand, the combination of more US supply and a stronger dollar would also mean producers with portfolios outside the US may be hurt by lower world oil prices. In the US, the cost of tradable oilfield services may also increase, because of both stronger activity and higher import costs. The degree of service-cost impacts will be determined by the extent to which the dollar appreciates, to which services are priced in dollars, and to which dollar-priced services adjust to offset dollar appreciation. And the benefits of a lower corporate income tax may be muted to the extent producers have carryover net operating losses following several years of low prices, or to which independents may pay little cash income tax as they re-invest most of their cash flows in new production.

Refiners may be harmed by having to pay more for their crude inputs to turn into gasoline, diesel and other products—either because the domestic crude price rises or because they effectively pay a tax on imported crude. Refiners will see already-narrow margins squeezed to the extent they are unable to pass those higher input costs onto consumers. And refiners without the ability to export product will be harmed more than those that can.

On the other hand, the lower corporate tax rate and the full expensing of capital investments would be highly favourable for US refiners, which tend to pay relatively high cash taxes. Moreover, they should be able to pass most of the costs of higher input costs on to consumers, as has been the case during other periods of temporary blowouts in the WTI-Brent spread.

Higher pump prices

As refiners pass on higher WTI prices, consumers would see the price at the pump rise. As Phil Verleger explained recently, based on the historical relationship between oil prices and retail gasoline prices, that means the price at the pump would rise around $0.30 per gallon if the world oil price were $50/b. So for consumers, the BTA might have an effect similar to raising the gasoline tax, but rather than the revenue going to the government it would accrue to oil producers.

For the American economy as a whole, a policy that raises pump prices would seem to be a negative since the US is such a large consumer and importer of oil. Based on historical evidence, a $10/b increase in oil prices would be expected to slow the rate of US GDP growth by around 0.2 percentage points relative to the baseline, as higher spending on petroleum leaves consumers with less disposable income to spend in other parts of the economy and raises costs for firms. A $0.30 price increase at the pump would reduce the median family's disposable income by $300 to $400 a year.

Yet the negative macroeconomic impact of higher gasoline prices may now be muted for two reasons. First, to the extent the US dollar adjustment is quick and full, world oil prices may fall—in a stylised case, as noted above, by a one-to-one ratio that would leave US oil prices unchanged. Second, even if US oil prices rise, the greater share of oil in the economy because of the shale revolution has upended established ways of thinking about the macroeconomic benefits of lower oil prices. Indeed, a recent paper for Brookings by two leading economists found that the boost to consumer spending from the 2014-15 oil-price collapse was almost exactly offset by the reduction in oil-related investment, which has risen as a share of the economy in the past five years. Economists at Goldman Sachs found the oil-price collapse was actually a net negative for the US economy.

While there are distributional concerns with higher oil prices, from the standpoint of GDP alone, the shale revolution may mean that oil prices can be too low as well as too high.

It is far from clear whether the BTA will become law. White House Republicans, notably Speaker Paul Ryan and Ways and Means committee chairman Kevin Brady, are strongly supportive, the Senate seems more mixed, and it is unclear what the Trump Administration's position will be. The business community is divided, as well, with large import-dependent retailers like Wal-Mart and other sectors (including independent refiners) opposed. On the other hand, the BTA might raise significant tax revenue in the 10-year budget window (although could worsen the long-run deficit if the trade imbalance narrows or reverses), and there are few other options in play to help offset the cost of lowering the corporate income tax rate.

Trade response

It is also unclear whether, even if it becomes law, the BTA would be found illegal under World Trade Organization (WTO) rules. Proponents of the BTA argue that WTO rules allow border adjustments in the case of VAT, a form of tax widely used around the world. WTO rules, however, only permit border adjustments on indirect taxes (for example, on sales or value added), but not on direct taxes (such as those levied on income or profits). Moreover, an important difference between VATs and the proposed border-adjusted cash-flow tax is that wages are included in the former, but excluded from the latter. Without other corrective measures, many trade lawyers argue that the BTA would thus discriminate against imports under WTO rules. Many economists, however, argue that if the WTO considers a BTA based on economic logic, there is no difference economically between a BTA and a VAT with a wage subsidy and a border adjustment, which is allowed under WTO rules.

Regardless, if the BTA is sold politically in the US as a protectionist boost for the country's competitiveness, others could decide to retaliate unilaterally even before it reached the point of a WTO ruling. The possibility of a tit-for-tat trade war developing following a BTA is another risk for industry to consider, especially given the liberalisation of US rules for oil and gas exports and its significant energy trade.

In short, if a BTA is adopted, the effects on the oil and gas sector, and global economy and geopolitics more broadly, would be far-reaching. World oil prices are likely to decline and US prices to rise, but the extent of each will depend on how quickly and completely the dollar adjusts, how sharply the US can ramp up oil output in response to higher prices, and how other producing countries respond to higher US output and a stronger dollar. Who wins and who loses among energy firms will vary based on many company-specific factors like their global production portfolio, upstream versus downstream activities, tax liability, share of upstream cost structure in local currencies, ability to export or need to import, and more. Geopolitically, producing countries may be harmed by a price decline and may see further fiscal strains from a stronger US dollar. In the US, consumers would likely see pump prices rise, acting as a drag on the macroeconomy that would be offset, at least in part, by increased economic activity in the oil patch as WTI rises. All these energy-sector-specific pros and cons, of course, must be viewed in the context of the much broader economic effects of a dramatic shift to a new system of corporate taxation.

In conclusion: A mooted border tax would likely strengthen the dollar and may buoy some oil producers. But it could raise US pump prices, be bearish for world crude markets and disruptive to geopolitics, and spark tit-for-tat trade spats.

The Pros and Cons of the Canadian Keystone XL Pipeline

When the Keystone XL pipeline was first proposed more than eight years ago, Russ Girling, TransCanada's chief executive (he was chief operating officer at the time), probably didn't imagine the bruising battles ahead, or that it would be president Donald Trump signing off on the project's presidential permit in 2017. But Girling was positively beaming as he watched Trump announce the approval of the permit in a 24 March 2017 Oval Office ceremony.

That Trump signed off on the line—which would move as much as 830,000 barrels a day of oil sands crude from Alberta to the Gulf Coast — wasn't a surprise, coming at the end of a self-imposed 60-day re-evaluation period in which the verdict was never in doubt. Still, it was no doubt sweet vindication for TransCanada after being denied by the Obama administration and seeing #KXL become a battleground in a much larger war over climate change and the future of fossil fuels.

However, the presidential permit is hardly the end of the line for the project.

For one, oil markets look a whole lot different than they did in 2008, when barrels from the oil sands were in high demand and producers were desperate for new outlets. Oil prices are half what they were then, the shale industry has disrupted global oil supply dynamics, and new pipeline projects have emerged as competition, which has shaken up the picture on both ends of the pipe.

In Alberta, there simply aren't as many barrels to go around. Lower-for-longer oil prices have meant that big international players have slashed oil sands investments as returns have withered. This, in turn, is raising doubts about the ambitious growth forecasts that justified Keystone XL in the first place. Newly approved pipeline projects that aim to take oil to Canada's west coast and south to the US will be competing for those barrels as well. On the receiving end, there is growing doubt about the long-term demand for the oil sands' high-cost, and carbon-intensive, barrels.

TransCanada has acknowledged how much the landscape has changed. "The shippers, they have a different price environment. They are operating under a different supply forecast. There's different competition out there. So the shippers are going through their own analysis," the head of the company's liquids pipeline business Paul Miller told analysts in February 2017. The company is confident those producers are still onboard and will commit to keeping the pipeline full. It will find out in the coming months.

It isn't just shifting markets that TransCanada has to contend with. The environmental groups that have stymied Keystone XL are spoiling for a fight over the project with the Trump administration. Lawsuits are already being drawn up over how the Trump administration went about approving the project. Win or lose, those suits could keep the pipeline tied up in the courts for months, or even years, to come. "This project has already been defeated, and it will be once again," the Sierra Club said in a statement.

And while TransCanada has the Trump administration on side, it still has to win over the states Keystone XL will pass through—Nebraska in particular. Nebraska's Public Service Commission, a state regulator, now holds the fate of the $8bn project in its hands. It will hold a series of public hearings over the summer that will no doubt draw boisterous opposition from green groups and landowners opposed to having the pipeline laid down across their land. Girling hinted at the tough slog ahead during the White House ceremony, telling Trump "we've got some work to do in Nebraska to get our permits there" after the president blithely asked when construction would start.

The Nebraska decision won't come until at least September. The company has said construction won't start until "well into 2018", which would mean first oil flowing through the pipeline in 2020 at the earliest.

So for all the exuberance and enthusiasm for KXL coming from the White House, it may ultimately prove to be too little, too late. Therefore, the challenges are not over for the pipeline which will run from Alberta to the Gulf Coast.

America's Oil Export is up in 2017

Oil tankers and liquefied natural gas carriers are not a new site in ports along the US' Gulf Coast, long a vital hub in the global energy trade. But the direction of traffic is new. Those ships now often leave US shores laden with American crude, fuel, liquefied natural gas and natural gas liquids. US energy is making its way to all corners of the globe, disrupting long-established trade routes.

One morning in late March 2017, for instance, saw the Gallina and Valencia Knutsen LNG tankers—both members of Shell's fleet—filling up at Cheniere Energy's Sabine Pass export facility in Louisiana, ready to ferry more super-chilled US shale gas to consumers in Europe and Asia. At the same time, just up the coast in the Houston Ship Channel, two newly built very large ethane carriers were being loaded down at Enterprise Product Partners' Morgan Point ethane loading terminal—the JS Ineos Ingenuity bound for northern Europe and Reliance Industries' Ethane Emerald, destination India. Neither facility existed 18 months ago, but they've been built as part of a multi-billion-dollar export infrastructure construction boom. It's turned a surge in US oil and gas production into a flood of exports.

The numbers are staggering considering how little energy the US exported just a decade ago. Last year was a record one for US energy exports on all fronts, even as domestic output slipped for the first time in six years. Refiners sent 2.97m barrels a day of refined products abroad after sucking in a record 16.2m b/d of crude. Oil shipments also hit a fresh high after export restrictions were lifted in late 2015, with 0.52m b/d being sent abroad. Booming NGL exports have been mostly overlooked. But the rise has been dramatic, reaching 1.2m b/d, more than twice what it was just three years ago, shaking up the global trade in petrochemical feedstocks.

Total liquid fuel exports were 5.19m b/d, nearly four times higher than a decade ago. Natural gas exports also hit a fresh high of 6.3bn cubic feet a day, nearly 10% of total US consumption.

America's refiners, sucking record amounts of cheap crude from domestic and foreign fields, have unleashed a wave of fuel products onto global markets. They've found especially strong demand in nearby Latin American and Caribbean countries, where US refiners have filled the gap left by the region's struggling national oil companies. Of the 0.63m b/d of gasoline exports in 2016, 330,000 b/d—more than half—went to Mexico. There, Pemex's financial woes have left its creaky refineries producing the least amount of product in more than 20 years: output is down 400,000 b/d since 2013 alone. Most of the rest of America's gasoline exports went to Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador and Canada, with just a trickle finding its way to Asia, where Chinese and Indian exports are more competitive. It has been a similar story for diesel, with most of the 1.19m b/d in exports going to nearby Latin America markets.

Heavy demand from Latin America should linger through 2017, at least. State oil companies, the region's main fuel suppliers, are struggling to recover from the downturn, and what little cash they have is going towards their upstream businesses, leaving little left to invest in refineries that aren't able to meet demand. An end to price subsidies in Mexico could see demand fall over the course of the year, though data from Pemex shows fuel sales held up well even amid violent protests over the higher prices in January and February 2017. Margins for US refiners have remained strong, giving them an incentive to keep running at around 90% of capacity. Maximising output should translate into yet more foreign sales.

Although US fuel products have seen higher volumes, crude oil exports have drawn the headlines. Last year (2016) was the first full year of unbridled crude exports after congress lifted the 1970s-era restrictions. The fall in US output—around 1m b/d from the peak in April 2015 to mid-2016—likely hurt overall volumes. So too did a narrow Brent-WTI premium of around $0.41 a barrel, after blowing out to as much as $20/b in recent years, which left little room for arbitrage. But the 0.52m b/d in exports was still up 12% from 2015, and a record.

New exports, new markets

The bigger change, however, was that US oil was able to find its way to markets around the world, reflecting broad demand for the light sweet crude coming out of US shale oilfields. Before the lifting of the ban, nearly all exported US crude went to Canada, which held a valuable exemption from the long-standing restrictions. In 2016, US oil found its way to 26 different countries, though Canada remained the biggest buyer, pulling in nearly 60% of exports. The Netherlands, which funnels crude throughout Europe, was the second largest buyer at 38,200 b/d.

Italy and the UK were also sizable importers. Curaçao, where Venezuela's PdV blends its own heavy oil with US light oil for re-export or to feed its refinery on the island, was the third-largest buyer.

Early 2017 figures point to rising crude exports as production picks up and new infrastructure is built as oil fills the gaps left by Opec's cuts. Exports for the first quarter were 0.775m b/d, compared with 415,000 b/d over the same period in 2016. Rising output from the Permian is helping push crude exports to new highs. Most of the Permian's 2m b/d-plus in output is linked via pipeline to the Gulf Coast, which is saturated with light tight oil. Domestic supplies have already backed out virtually all imports of other light grades in the Gulf Coast, leaving the new Permian barrels little space except for the export market.

With activity and output picking up in the Permian, more barrels are likely to be pushed onto international markets from the Gulf Coast. Nearly 100 new rigs have been added in the basin over the year and, according to Energy Information Administration projections, output is up around 200,000 b/d from January to April 2017, putting it on pace for a rise of around 0.6m b/d from end-2016 to end-2017. That is in line with the double-digit growth the basin's largest drillers see this year.

Midstream companies are racing to keep up with Permian producers, building new pipelines from the fields to new and expanded storage facilities and terminals on the coast. Enterprise Products Partners is building a 450,000-b/d pipeline from Midland to its storage hub in Sealy, Texas, where the crude can then be sent on to refineries or export terminals. It's the largest new pipeline out of the Permian and is due to start up later this year (2017). At least a half dozen other companies, including Phillips 66, Magellan Midstream and Centurion, are expanding their ports to add millions of barrels of new storage and new docks—all expecting that exports will rise sharply in the coming years. Enterprise Product Partners said in a recent presentation that exports of light oil could top 2m b/d by 2020 if output continues to rise.

NGL surge

A by-product of the shale revolution has been a surge in the production of natural gas liquids—especially propane and ethane. Propane is used by consumers as a heating and cooking fuel and as a petrochemical feedstock, while ethane is used almost exclusively in petrochemical facilities to make ethylene. US demand for propane has been stagnant, however, so as shale drilling has picked up over the years, producers have increasingly had to look abroad. Just five years ago, a trickle of US propane shipments to Canada and Mexico were the only exports. By December 2016, exports topped 1m b/d as Asian petrochemical facilities, keen to diversify from their reliance on Middle East suppliers, tapped into the US' relatively cheap and abundant supply.

Large-scale ethane exports are being made possible by investment in new export terminals and specialised ships to transport the volatile fuel across oceans. Enterprise Product Partners opened its 200,000-b/d Morgan Point facility in September 2016, which followed the opening of the smaller 35,000-b/d Marcus Hook terminal in Pennsylvania, to take advantage of rising ethane output from the Utica and Marcellus shales. The facilities have tripled the US' export capacity, adding to existing pipeline infrastructure into eastern Canada, to around 400,000 b/d. Ineos, a European chemicals company, and Reliance Industries, the Indian conglomerate, have both built first-of-their-kind large ethane carrying ships to ferry a steady supply of American ethane to their facilities back home. Ethane exports hit a record 168,000 b/d in December 2016, up from zero in 2012, after the Morgan Point terminal opened, and should continue to rise over the next couple years.

Last year (2016) also broke new ground for US LNG exports, with the first shipments from the Lower 48 starting up at Cheniere's Sabine Pass plant. Combined with rising exports via the pipeline south into Mexico, it helped flip the US into becoming a net gas exporter for the first time ever, at least temporarily. LNG exports will continue to rise this year thanks to the commissioning of Sabine Pass's third and fourth trains, which will see the plant sucking in as much as 3bn cf/d of gas at times, around 5% of total US gas consumption, with an average of around 2.2bn cf/d, according to Barclays, a bank. In the latter half of the year, eyes will turn to Dominion's Cove Point export plant in Maryland, which the company says is 84% complete and due to start up in late 2017.

As Sabine Pass and Cove Point ramp up, the US is on pace to flip to a net gas exporter in 2018. It would be the first time since the 1950s and a potent symbol of the US' changing energy fortunes.

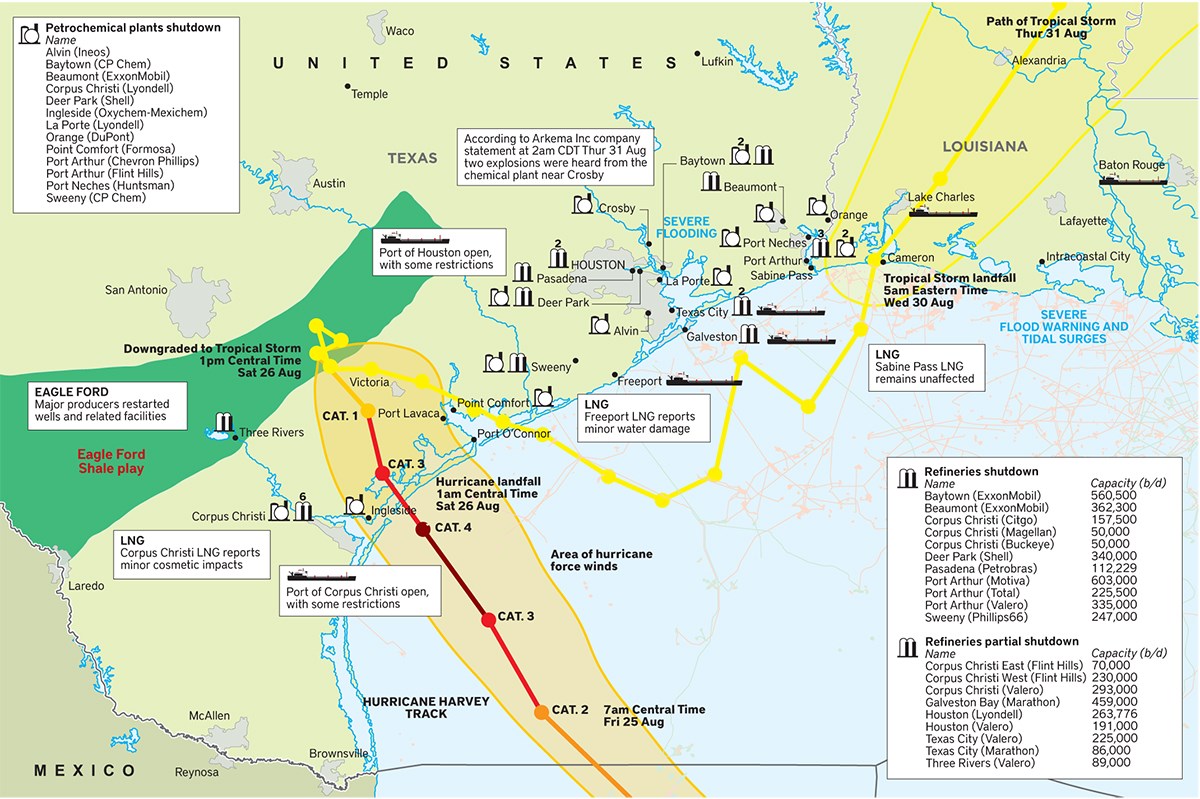

Hurricane Harvey's energy impact

In case you missed the wall-to-wall coverage, Hurricane Harvey slammed into the Gulf Coast, the heart of America's oil and gas industry and one of the world's largest energy hubs, on 25 August 2017. Torrential rain is expected to keep falling on Houston and surrounding areas throughout this week.

The immediate concern is for the thousands affected by the flooding. But the fallout on energy markets will be great: supply, energy infrastructure and demand have all already been significantly affected by the storm.

Gasoline and other fuel prices quickly jumped more than 5% as the scale of the disaster became clear and refineries along the coast were shut down. WTI crude prices fell more than 2%, and the benchmark's discount to Brent spread to more than $5 a barrel for the first time since mid-2015, on reduced demand from Gulf Coast refiners.

Around 2.2m barrels a day of processing capacity was taken offline over the weekend, roughly 45% of Texas's Gulf Coast capacity and a fifth of the capacity in Padd 3, the broader Gulf Coast region. Most of the closures were focused around Corpus Christi, which suffered a direct hit from the hurricane. The city's five refineries and condensate splitters were all closed, including the Citgo, Valero and Flint Hills' major refineries, though none reported serious damage.

Most of the facilities are likely to try to reopen by the end of the week, which should mean a relatively short interruption. Still, due to widespread disruptions of personnel, power and infrastructure it will take many more days, if not weeks, for full capacity to be regained.

Bulging US crude and product inventories will help fill the gap, and could even accelerate a stock drawdown long sought by oil bulls and Opec ministers who have closely tracked the US' weekly inventory reports for signs of the market rebalancing.

But further refinery outages may lie in store. Some models predict Harvey will turn up the coast towards Louisiana, where another 3.7m b/d of crude processing capacity would sit in the storm's destructive path. Analysts at Tudor Pickering and Holt, the investment bank, have warned this could shutter 30% of the nation's refining capacity. Others say the tempest, which has been downgraded from a Category 4 hurricane to a tropical storm, would still pack enough punch to force facilities to shut down by the time it reached Louisiana.

Harvey is also disrupting oil output and the pipelines that ferry crude and products around the region. Nearly 20% of the Gulf of Mexico's production was shut in over the weekend—430,000 b/d—after a number of operators pulled personnel out of harm's way. However, no offshore platforms appeared to suffer serious damage and production had already started coming back by Monday afternoon, when the outage was down to 330,000 b/d, according to the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement.

While hurricanes are nothing new for Gulf producers, this was the first big storm to hit a shale field—the Eagle Ford. BHP Billiton, ConocoPhillips, Murphy Oil, Statoil and others all evacuated their Eagle Ford sites and closed operations. The Texas Railroad Commission estimated that 300,000 to 0.5m b/d of the Eagle Ford's roughly 1.3m b/d in total output was offline. The full extent of the damage to well sites won't be known for days until the flooding recedes and workers are able to reach the area.

A major new oilfield in Hurricane Alley clearly increases the supply risk during such storms—the total production shut down between the Gulf of Mexico and Eagle Ford was as high as 0.9m b/d, close to 10% of total American output.

The storm did not affect operations in the Permian, which is in west Texas, but a lot of the infrastructure that brings Permian and other crudes to the Gulf Coast's refineries and ports passes through Houston. Much of this has also been shut. Magellan Midstream closed 0.675m b/d of Permian takeaway capacity when it shut down the Longhorn and Bridgetex pipelines, which pass through Houston. The company had no timetable for a return to normal operations as of 28 August. WTI Midland, a Permian Basin sweet crude, was trading at a $0.50 discount to WTI on Monday, a much steeper discount than usual, according to Platts. A prolonged outage at one of the Permian's major pipelines could stall Permian growth and hit producer revenues.

Harvey's disruption of major ports will also disrupt the region's booming oil, fuel and gas trade. US oil and fuel exports are at record highs and will be disrupted with Texas's major ports closed. Fuel exports have averaged more than 5m b/d over the first half of this year, compared with around 1.3m b/d when Hurricane Rita, the last major hurricane to strike Texas, hit in 2005. During Rita, fuel exports dropped by a third and it took three months to return to pre-storm levels. That poses a particular risk to Mexico and other Latin American markets that have grown reliant on fuel imports from the US.

Therefore, a storm-ravaged Gulf Coast faces a large and complex recovery that could take longer than energy investors expect.

U.S. Railroads Refusing Demands for Oil Storage in Rail Cars-COVID 19 syndrome

Railroads are clamping down on rising demand from oil companies to store crude in rail cars due to safety concerns, sources said, even as the number of places available to stockpile oil is rapidly dwindling.

Oil demand is expected to drop by roughly 30% this month (April 2020) worldwide due to the worsening coronavirus pandemic, and supplies are increasing even as Saudi Arabia and Russia hammer out an agreement to cut worldwide output. Storage is filling rapidly as refiners reduce processing and U.S. exports fall.

Globally, storage space for crude could run out by mid-2020, according to IHS Markit, and most U.S. onshore storage capacity is expected to fill by May, traders and analysts said.

However, railroads including Union Pacific and BNSF, owned by billionaire Warren Buffett, are telling oil shippers that they do not want them to move loaded crude trains to private rail car storage facilities on their tracks due to safety concerns, three sources in the crude-by-rail industry said.

The railroads are telling clients that tank cars are not a prudent long-term storage mechanism for a hazardous commodity such as crude, and do not want to put a loaded crude oil unit train in a private facility and potentially create a safety hazard, they said.

Federal rules typically only allow crude in rail cars to be stored on private tracks. There is no federal data on how much oil is regularly put in rail storage, but analysts said it is very little.

“Most federal regulations require rail cars loaded with crude oil to be moved promptly within 48 hours. Therefore, federal regulations discourage shippers and railroads from leaving crude oil in transportation for an extended time,” transportation lawyers at Clark Hill LLC wrote in an article Thursday.

BNSF did not respond to several requests for comment. Union Pacific declined to comment.

Nearly 142 million barrels of crude moved via rail in the U.S. in 2019, representing about 10% of what is transported via pipelines, according to the U.S. Energy Department. Unit trains, made up entirely of tank cars, can carry around 60,000-75,000 barrels.

Even on smaller or mid-sized railroads, known as short-lines, there may be capacity constraints or insurance coverage may not be adequate, the railroads have said, advising rail companies not to store oil.

“It is arbitrary, and is happening at a time when it (storage) is an option being heavily considered by all companies that have access to crude by rail right now,” one of the sources said.

As of September 2019, there was enough crude storage capacity in the U.S. for about 391 million barrels of out of about 700 million working capacity, excluding the strategic reserve, according to the U.S. Energy Department. However, U.S. stocks have risen by 32.5 million barrels in just the last 4 weeks, including a 15-million-barrel gain in the latest week, the most ever due to COVID 19 effect.

Crude-by-rail shipments were not economic when oil prices were high but are expected to rise as prices have plunged. Loadings out of the Permian basin, the biggest in the country, slumped to about 12,500 barrels per day (bpd) in January 2020, the lowest in at least a year, before rising to about 13,200 bpd in February 2020, according to data from Genscape.

Demand is falling so swiftly that rail cars loaded with crude may not be accepted by the time they reach their destination three-to-five days later, leaving barrels orphaned without a storage option, one trader said.

Rates to lease rail cars have dropped sharply due to the crash in oil prices, making them more attractive for storage. Lease rates for rail cars have fallen from about $800 per month to about $500, said Ernie Barsamian, founder and CEO of The Tank Tiger, a terminal storage clearinghouse.