Energy Security Intelligence Research

ESIR

ESG STRATEGY RISK and COMPLIANCE PLANNING AGENDA 2050

SAUDI ARABIA

VISION 2030 TARGET

Weaning Off Oil

- SAR0.6 trillion in non-oil revenue by 2020 (from SAR163.5bn in 2015

- Newfound Renewable

- 9.5 gigawatts of renewable energy generation by 2030

- SAR97bn increase in the mining sector's contribution to GDP by 2030

- Digging Deep

Since the drop in oil price, Saudi Arabia's problems are mounting with youth unemployment, demographic changes, an ailing King and corruption in Aramco-the state NOC.

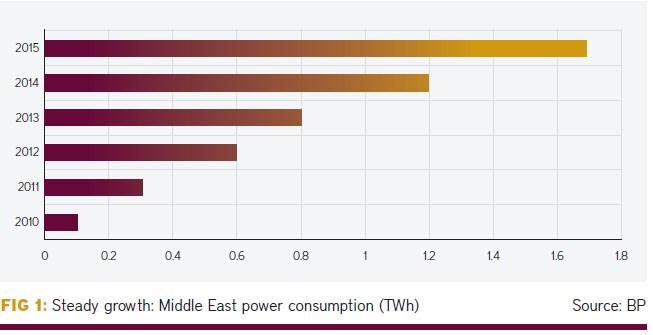

There are other threats to the Kingdom, though a long-term threat, a report issued in 2013 from Citi Bank, claimed Saudi Arabia could soon run out of oil to export. About a quarter of Aramco's oil output is already consumed domestically, much of it to feed power generators. But with electricity demand rising by 8%-a-year, said Citi Bank, "if nothing changes Saudi may have no available oil for export by 2030".

The caveat was crucial, because the Kingdom isn't going to watch its lucrative oil-export business die slowly. Eroding subsidies that make Saudi oil and natural gas prices among the cheapest in the world would be the obvious answer-though managing that transition was the arrival of "VISION 2030" aims to transform the Kingdom with the leadership of the ruling Saud family frets about any signs of unrest will be difficult. Powerful groups within the country as well as the poor currently benefits from the status quo, so opposition to subsidies reforms would be strong.

Saudi Arabia's Aramco Global Operations

Cairo tries to calm riled Riyadh

Egypt's growing political independence is propelling a fundamental shift in its historical energy alliance with regional hegemon Saudi Arabia, and the change brings the potential to scar. A growing list of political irritants for Saudi Arabia is likely the reason the kingdom halted a $23bn oil-products package last October 2016, just a few months after it agreed the five-year supply deal in April the same year.

Riyadh was rankled by Egypt's reluctance to back the Saudi-led coalition against multiple groups opposing the Yemeni government since 2015, notably the Houthis, a Zaidi Shia group from northern Yemen. But relations were particularly soured in October following Egypt's support of a Russian UN draft resolution on Syria and an offer by Iran, Riyadh's primary rival in the region, to supply Cairo with oil products. A deal with Tehran would help plug Egypt's oil-supply gap and help transform the countries' oft-awkward relations into a more collaborative dialogue. It would also likely dash Cairo's bid to accelerate Riyadh's delivery schedule.

Saudi Arabia's sensitivity to Egypt's political loyalty is no shock. The kingdom has long provided Cairo with financial support and backed President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi's military coup in 2013.

Trying to unwind tensions in December, Egypt's foreign minister, Sameh Shoukry, publicly reaffirmed the country's "special relationship" with its powerful ally and the Egyptian government approved the controversial transfer of two islands, Tiran and Sanafir in the strategic Gulf of Aqaba, to Riyadh. The island transfer, which needs approval from Egypt's higher administrative court, sparked protests in Egypt last April. Opponents said the deal was a land sell-off, as it was announced at the same time as Egypt received another aid package from Saudi Arabia. Riyadh's delayed oil products also forms part of a financial-aid package in which Egypt will receive funding for those products, to be repaid over 15 years at 2% interest.

Under the products deal, Saudi Aramco increased supply from 0.5m tonnes a month to 0.7m t/y, or about 180,000 barrels a day. The volumes are split between 400,000 tonnes of gasoil, 200,000 tonnes of gasoline and 100,000 tonnes of fuel oil. The agreement was to be a corner-stone effort by Tarek el-Molla, Egypt's petroleum minister, to slash the cash-strapped country's soaring fuel-import bill. The cheque came to $8.6bn in the 2015-16 annual budget.

Cairo's efforts to limit the financial guesswork in the energy budget are being hampered by state company EGPC's need to issue a growing number of oil tenders for spot cargoes to help meet domestic demand. Demand in the first nine months of 2016 was 9.2% higher than in the same period last year, according to the International Energy Agency. Consumption in September averaged 0.95m b/d, which is 125,000 b/d higher a year earlier. It is expected to average 0.93m b/d in 2017 and Egypt's appetite will only intensify: the country's population of 92.2m is forecast to rise to 100m by the early 2020s. Cairo needs Riyadh to play ball.

But Saudi Arabia must also consider the ricochets of its political plays. The decision to pause Egypt's oil products package echoes the kingdom's resolution to halt production at the 300,000-b/d Khafji field in the Neutral Zone in October 2014 amid discord with Kuwait, which equally shares the zone. Only now, nearly 30 months later, are tangible signs emerging that production at Khafji and neighbouring Wafra, also in the Neutral Zone, may resume.

Lower oil prices have particularly exposed the kingdom's economic Achilles' heel and most likely encouraged Saudi Aramco to pencil in an IPO for next year, which could raise up to $100bn. Crucially, the IPO could knock down the bricks of the impenetrable wall that has always hidden the Kingdom's oil and gas reserves data. In the meantime, Riyadh garnered some diplomatic gold stars for orchestrating the first global oil deal between Opec and non-Opec producers since 2001 and for taking unprecedented steps to reduce energy subsidies.

Major changes this year-political, economic and social-will continue to transform the Saudi Arabia that the energy market and investors are so familiar with. As the kingdom enters uncharted territory, Riyadh must manage its allies with care and use its power plays wisely.

"A delayed and much-needed $23bn oil-products package from Saudi Arabia to Cairo is part of a complex political narrative with few signs of an easy fix"

Saudi Arabia pushes ahead with Aramco IPO

Lower oil prices have exposed Saudi Arabia's Achilles' heel and, as global environmental legislation tightens, the kingdom must deal with the problem. The 84-page Vision 2030 is designed to do just this, breaking the country's addiction to oil (and especially oil revenue). The part privatisation of Aramco, as anyone who follows global energy now knows, is part of the effort.

A firm that currently provides 90% of government revenue, hope Riyadh's strategists, will evolve into an energy and industrial conglomerate operating under the umbrella of the Public Investment Fund (PIF), generating wealth indefinitely. Aramco will follow the right path in an age-old fork in the road-change, or be changed.

Much remains to be done, especially considering the speedy schedule. It was only in January 2016 that Saudi's deputy crown prince Mohammed bin Salman, the architect of plans to enhance Riyadh's influence beyond oil diplomacy, announced plans for an initial public offering of 5% of Aramco. He wants the flotation complete in the second half of 2018. The clock ticks.

The IPO marks the biggest shift in Aramco's history since 1980, when the Saudi government paid its partners $1.5bn for their 40% holding in the firm, leaving it fully nationalised. The changing dynamic was marked last year too, when Ali al-Naimi, 21 years in the job of oil minister, handed the ministry's reins to Aramco's chairman, Khalid al-Falih.

As it readies itself for the sale, Aramco and Saudi Arabia are having to relearn some international norms. The firm is shedding some secrecy surrounding the true size of its oil and gas reserves—an essential requirement if it aims to raise up to $100bn from the IPO. The cash injection would come as the kingdom rolls out unprecedented energy-subsidy cuts in the face of a $53bn deficit for 2017. It's impossible not to see the IPO plan as part of the broader thrust to transform an economy that has become all too accustomed to old rentier methods of doing business.

Aramco is considering listing on up to three exchanges. Riyadh's Tawadul is likely, and London, New York, Tokyo and Hong Kong are also in the running. It is making efforts to open the books in response to valid criticism from global investors. Aramco will disclose its 2017 annual statements before the listing, while results of the first independent audit of its oil assets earlier this year were in line with internal estimates of 265bn barrels. That added to the company's sheen as a highly efficient group—not a reputation it shares with many other national oil firms—will shave time as it prepares for Wall Street's scrutiny.

Some investors herald the IPO as a new chapter of financial acumen that could trigger opportunities in other state-owned entities in the Gulf. Others fret that a dangerous precedent could be set if an excitable financial market agrees to move ahead without full transparency. Some doubters see an elaborate PR ruse.

Financial relief

But among the rush of bankers seeking a slice of the IPO business, the consensus is that Riyadh's course is set, even if the timing might depend on the oil price. If the market takes the kind of bearish turn seen in January 2016, when Brent futures dropped to a 12-year low, a sale would bring instant financial relief, encouraging Aramco to stick with the 2018 timetable. But that presupposes a derailing of the Opec-non-Opec agreement struck late last year: there's little sign of that happening, yet, and Aramco has a great deal of sway over the deal's success.

In fact, to shore up the deal, Falih has said that Saudi Arabia could cut even more than it signed up to in November. This is no idle threat, given the wealth of supply at its disposal should Riyadh think the Opec agreement is unravelling. Aramco's output peaked at 10.67m barrels a day last July, with the International Energy Agency (IEA) estimating that the company could easily and quickly pump 11m b/d if necessary. Mohammed bin Salman cites capacity of 20m b/d as a realistic long-term goal.

But what if a much firmer rally grips the market before the scheduled 2018 IPO?

The rising oil price would, in theory at least, increase Aramco's valuation. But by generating more oil-export income for the kingdom it could also sap some of the government's enthusiasm to carry out unpopular reforms, such as those to energy subsidies. And the urgency to sell off some family silver would be less acute too.

Educated guestimates

Many believe the 2018 IPO has been a motivator for Saudi Arabia's re-intervention in oil markets—support for Brent would garner more interest in the sale. But if the IPO is interpreted just as a method to recoup money lost by falling oil income, would a new rally kill off the idea?

Even without a sharp recovery (or another fall) in the oil price, valuing the 5% stake is difficult. The $100bn guestimate most commonly cited would make the value of the IPO four times bigger than the $25bn record held by Chinese internet retailer Alibaba's 2014 IPO.

But this view of the Aramco stake depends on Mohammed bin Salman's and some analysts' $2 trillion estimate of market capitalisation of the whole company. Qamar Energy, a UAE consultancy, reckons the value of the 5% up for grabs could slide to around $20bn once a 20% royalty and 85% tax rate are deducted. Aramco's chief executive, Amin Nasser, reassured investors in mid-January that tax will be adjusted to make the deal more attractive. But details are still thin.

Investors will also have to account for Aramco's new growth plans and his ability to steer the firm through choppy politics. Nasser wants to double Aramco's refining capacity, including its stake in foreign operations, to 10m b/d. Aramco's presence in the US through its Motiva joint venture with Shell, established in 1988, should help the company navigate President Trump's "America First" policy and even play on his pro-oil stance to expand the Saudi firm's downstream and distribution in the country. Plans to dissolve Motiva mean Aramco would have full control of the 0.6m-b/d refinery at Port Arthur, Texas, the US' large such facility.

For Aramco, the greater gains are to be had to the east anyway. In Asia, the Saudi firm must safeguard its coveted client list against intensifying competition. The company exports 65% of its oil and a third of its refined products to the continent. The US, able to ship its oil and gas through the recently widened Panama Canal, will only add to the competition—especially while Aramco and other Opec producers limit their output. Russia last year nudged Aramco aside to emerge as China's biggest crude oil supplier, selling it 1.05m b/d (compared with Aramco's 1.02m b/d). Exports to China from Iran, Riyadh's primary rival in the Middle East, climbed by 18% to a record high of 0.63m b/d in 2016.

Closer to home, Aramco ramped up production capacity at the Shaybah oilfield last May by 250,000 b/d to 1m b/d with plans to lift production capacity at Khurais by 300,000 b/d to 1.5m b/d next year. Another 250,000 b/d of capacity could be unlocked relatively quickly in the Neutral Zone that Saudi shares equally with Kuwait, if the political spat stretching back to October 2014 is resolved.

By national-oil firm standards, Aramco's execution of upstream oil projects is exemplary. But Aramco's gas development plans have lagged—a strategic frailty considering Saudi policy does not allow gas imports.

As gas accounts for only half the kingdom's power generation, the rest is met through domestic oil supply, soaking up 1m b/d or so that could otherwise be exported. Aramco's plan to double total production capacity for natural gas, from 12 billion cubic feet a day over the next decade, would help fix this—and reward investors interested primarily in Aramco's ability to sustain oil exports, regardless of rising local power-generation needs.

"The state firm is making the right noises about its privatisation, but the clock is ticking and market fundamentals could still shift".

Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States Renewables Energy Ambitious

Energy leaders in the Middle East were listening when Shell warned in 1991 that climate change was happening faster than at any time since the end of the ice age. But the volume was not turned up high enough. A little over a decade later, rising oil prices and a booming industry meant that doors in the global corridors of power were largely closed to environmentalists' warnings. The Gulf's carbon footprint, exacerbated by generous fuel and energy subsidies, soared.

Things are changing—right at the heart of the oil world. Saudi Arabia and the UAE, both core Opec members, have earmarked $50bn and $163bn for spending on greener energy by 2023 and 2050, respectively. The eco-friendly tone of Gulf governments' new national visions means state-owned entities—Saudi Aramco, Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (Adnoc), Emirates National Oil Company (Enoc), Qatar Petroleum and Kuwait Petroleum Corporation (KPC), to name some—must do as their masters wish. A greening of the Gulf is underway.

What prompted the shift? For one thing, the fragmented politics and unattractive costs that used to snuff out oil companies' appetites for renewables have eased. Globally, years of momentum are now built into efforts to fight against climate change—Gulf countries may have joined the movement late, but joined they have. For another, it saves money. The greening goes hand in hand with reducing subsidies too, another feature of the region's changing energy economics—and no less part of the effort to free up energy wasted at home so it can be sold more lucratively abroad.

Middle East oil producers—especially state-owned entities with socio-economic checklists to meet—have shown unprecedented support for the Paris Agreement since its inception in December 2015. And there is no sign their position will alter much, despite worries that the US may now falter on its commitment to the historic climate deal, which aims to keep global temperature rises this century well below 2 degrees Celsius. The world's most powerful politician might not be convinced by climate science but big oil companies are. Middle East energy leaders have an opportunity to build a bigger presence—with a bigger voice—in the emerging green economy.

$50bn - Amount Saudi Arabia plans to spend on renewables by 2023

Meeting local needs is also paramount. And the need is great. The Middle East Solar Industry Association expects the region's total electricity demand to exceed 1,000 terawatt-hours this year alone. Gulf power capacity must rise about 8%, or 69 gigawatts, as soon as 2020, involving $85bn of investment, according to Apicorp, a bank. Longer term, population and economic growth will demand even more electricity. Cairo, for example, will add 0.5m people to its population by end-2017, Qatar's 2.5m population is expected to rise eight-fold by 2050; and Dubai's to double to 5m by 2030.

Luckily for the Gulf, the cost of installing and using renewable technologies in the Middle East has plummeted, as it has elsewhere. Commercially available solar-panel efficiency worldwide jumped from 15% to 22% in the past five years, after two decades of near stagnation, according to the World Economic Forum (WEF), while capacity factors for wind turbines nearly doubled to 50% in the past decade. The UAE has spearheaded affordable solar: in September, Abu Dhabi set a world-record low price for large-scale solar power-¢2.42 per kWh.

The opportunities in renewables contrast with a growing sense of gloom about hydrocarbons in the Gulf. Oil prices remain low and global supplies are ample. Talk of "peak demand"—accurate or not—is troubling executives across the region. Notions of an era after oil infused the Saudi Vision 2030 and crown prince Mohammed bin Salman's desire to break the kingdom's "addiction to oil".

In that context, renewables could act as a life raft for the Middle East—the Gulf especially—yielding opportunities in a fast-growing segment of the energy economy and, if it helps meets local needs, free more crude oil for export. Mohammed bin Zayed, Abu Dhabi's crown prince, asked in 2015 if his country would be sad when it exported "the last barrel of oil". He answered his own question: "If we are investing in the right sectors"—he was referring to renewable energy—"I can tell you we will celebrate at that moment."

Rethinking extremes

For green investors, the Middle East's extreme climate offers largely untapped riches: 300 days of sunshine and desert winds are the ideal playground for new and cost-efficient solar technologies. It also offers a constant reminder of the climate-change threat. The temperature of 54°C recorded in Kuwait last year marked the highest level ever recorded in the eastern hemisphere and, considering questionable data gathering methods in the early 1900s, possibly the highest ever recorded on earth. Little surprise then that the Mena Climate Action Plan will nearly double the portion of the World Bank's financing dedicated to climate action up to 2020, to around $1.5bn per year.

With an economic tailwind behind them, renewables can take advantage of this political will. Cost is key—and even cheap coal is being overtaken. The average global levelised cost of electricity (LCOE) for coal has hovered around $100 per megawatt-hour for over a decade, but the cost of utility-scale solar photovoltaic in Mena—$600/MWh a decade ago—is now just as cheap. The LCOE for wind is even lower, at just $50/MWh, though PV might soon catch up there too: the International Renewable Energy Agency (Irena) expects solar's LCOE to fall by 59% over the next decade.

Oil-fired generation, often the mainstay for baseload power in the Gulf, is no solution, despite the fall in price. Increasingly strict environmental policy and competition in the export market mean burning crude oil or fuel oil domestically is a costly waste. Saudi Arabia, for example, burns up to 1m b/d of Aramco's oil output to generate electricity for its 30m residents, at a cost of around $16bn a year based on recent prices.

Renewable oil recovery

In fact, renewables and oil enjoy an increasingly symbiotic relationship. For one thing, petrodollars are funding the investment in green energy. For another, renewables are also increasingly used to benefit oil in another way, through enhanced oil recovery (EOR).

Oman's Miraah solar-thermal plant is the best example. Using 36 glasshouses, it will generate 6,000 tonnes of steam per day to support state-owned and Shell-led Petroleum Development Oman's existing thermal EOR technology at the Amal field. The $0.6bn contract to create Miraah results in an 80% saving of natural gas at the field and should come online this year. To the west, al-Reyadah, a joint venture between Adnoc and Masdar, officially inaugurated the Mussafah facility last November. The first commercial-scale carbon capture, utilisation and storage facility in the Middle East, al-Reyadah will capture up to 0.8m tonnes a year of carbon emitted from Emirates Steel and pipe it to Abu Dhabi Company for Onshore Petroleum Operations for use in EOR at its Bab and Rumaitha fields.

But such projects—and the existing green energy plants that are already on line—pale in significance against the broader goals of the region's governments. The UAE launched its Energy Plan 2050 in January, with the aim of increasing clean-energy use by 50% and improving energy efficiency by 40%. According to the plan, by 2050, the UAE's energy mix will comprise 44% from renewable energy, 38% from gas, 12% from so-called "clean fossil" fuels (such as carbon capture and storage and new generation coal-fired power plants) and 6% from nuclear energy. More than 90% of the country's energy needs are now met by natural gas—a rising import bill that Abu Dhabi and Dubai are keen to minimise. Better cost management is paying off: Dubai-based Enoc has saved $7m since the launch of the Group's Energy and Resource Management programme in 2012.

The UAE's financial success in solar power is defying older notions that PV is a money sink. The Mohammed bin Rashid al-Maktoum Solar Park, under construction, will be the world's largest such site. Capacity for the $13.6bn project will reach 1GW by 2020 and 5GW by 2030—enough, say developers, to power 0.8m homes. On a smaller scale, the installation of rooftop solar in the UAE could reach 70MW this year alone—tenfold growth in just one year.

Not to be outdone, Saudi Arabia is seeking bidders for the first stage of its $50bn renewables plan to develop almost 10GW of renewable energy by 2023, with the first tender for 400MW of wind capacity and 300MW of solar. Qualified bidders were scheduled to present their offers for the projects from 17 April—the first major step towards the kingdom's goal for renewables to supply 30% of its power by 2030. Saudi Aramco and US firm GE delivered the first wind turbine to the kingdom last December. In keeping with Saudi's ambitious style, the energy ministry also aims to make its Renewable Energy Project Development Office the world's most competitive government-run programme.

$163bn - Amount the UAE plans to spend on renewables by 2030

On the other side of the Gulf, Iran has big plans too, calling for the addition of 5GW of renewable energy in the next five years and another 2.5GW by 2030. It is an ambitious strategy considering Tehran needs foreign investment—and even basic financing is tricky while some sanctions remain in place. Yet Tehran's appetite for change makes the unlikely possible. German company Athos Solar became the first investor to install and launch two high-performance greenfield solar-PV plants in Iran in early February. Athos provided 100% equity for the $21m project in the province of Hamadan near Tehran, with a combined peak output of 14MW. The speed with which the project was executed will be envied in established markets: Athos completed both greenfield plants just nine months after first contact with the Iranian developer. Iran's restricted financing options will narrow the field of potential investors, but companies with deep enough pockets will be welcomed.

Operations at Kuwait's first-ever solar power plant began last October at the Umm Gudair oilfield, where the $99m project will generate 10MW by an unspecified completion date. Half the power has been earmarked for the public electricity network as a step towards generating 15% of the country's energy needs via renewable sources by 2030. The other half has been allocated to supply state-owned Kuwait Oil Company's oilfield. Meanwhile, Morocco is aiming to have 600MW in operation by 2019, Jordan has 540MW of solar-PV projects under construction and Egypt plans to have 2.7GW of solar-PV capacity by 2020. Appetite for nuclear energy is also slowly emerging in the Middle East. As with solar, the UAE is leading the charge. Construction of the $24.4bn Barakah 1 plant is scheduled for completion in 2020, when it should meet up to 25% of the country's electricity demand and save up to 12m tonnes in emissions per year. But Saudi Arabia is being the most ambitious. The Kingdom plans to construct 16 nuclear power reactors over the next 25 years at a cost of more than $80bn and projects 17 GW of nuclear capacity by 2040. Egypt expects to finalise a contract to build a nuclear power plant with Russia's Rosatom by the end of this year, while the company's feasibility study for a $10bn contract for two 1000 MWe VVER units at Az-Zarqa in central Jordan is due by July, with the country's first nuclear power plant potentially operational by 2025.

The Middle East's enthusiasm for green energy is laudable, but it is a little late compared to global efforts. The European Union's Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) began in 2005, albeit initially on a frail note, while China and the US, especially California, have been slowly upgrading their green education for over a decade. The GCC states are holding their own in the Middle East as progressive thinkers, which is largely thanks to their pots of petrodollars from years of triple-digit oil prices pre-2014 now being invested in green research and development.

Although worldwide spending on clean energy last year fell, from $348.5bn in 2015 to $287.5bn, the drop was largely a reflection of investors getting more value for their buck. Technological advancements and efficiency led to a 19% increase in the amount of wind and solar energy connected to power grids around the world last year. Hold the applause, though. Irena estimated in 2015 that global annual investments in renewable energy would need to reach over $0.5 trillion in the period up to 2020, and then scale up to an annual average of $0.900 trillion between 2021 and 2030 to achieve green targets.

Saudi Aramco was the only Middle Eastern oil major who in late 2016 joined nine of the world's other biggest oil companies to invest $1bn per year to bolster energy efficiency, in addition to individual clean-energy projects. Given Aramco's supremacy in oil, sceptics said it was not more than a token gesture. Still, $1bn is some token.

Green investments require a new—and generous—way of thinking. The concepts and lingo borne in Europe are increasingly peppering business conversations in the Middle East, but it has been a relatively slow journey. In 2007, the European Investment Bank (EIB) issued the world's first green bond, labelled a Climate Awareness Bond (CAB), which was followed by the World Bank's first green bond in 2008. Green bonds, where the proceeds are applied to finance or re-finance new or existing green projects, evolved from being the remit of multilateral development banks to be an accessible mechanism for the public and private sector.

The global rate of green-bond issuances reached $60bn in the first nine months of 2016-150% of the total issuances in 2015, says the World Bank. While such bonds still account for just a slice of the $100 trillion global bond market, the increasingly savvy state-owned Middle Eastern oil companies are keen. Such methods of raising money enhance companies' reputations as sustainable and environmentally friendly brands-big ticks for Gulf countries' low carbon National Visions.

Not all green financial mechanisms are welcome. Singapore's launch of a carbon tax for refineries, power stations and other big emitters from 2019 has raised eyebrows in the Middle East. The tax could increase refiners' costs by up to $7 a barrel. This comes around the same time as refineries are trying to navigate the implications of the International Maritime Organization (IMO)'s decision to clean up shipping more quickly than previously planned. The IMO's sulphur cap on marine fuels used by ships must now drop from 3.5% to 0.5% by January 2020, instead of 2025.

But Singapore's move raises two crucial points for the Middle East and its booming refining sector. First, it highlights the value of funnelling cash into renewable-energy projects to avoid the inevitable budget-crunching impact of environmental policies. Second, it puts pressure on Middle Eastern oil and industry leaders to adapt before change is forced upon them—by more aggressive climate fighters in key markets like Asia. They must quickly identify solutions, for the options currently on the table hold little appeal; ETS, voluntary off-setting systems and carbon taxes, for example. Every year that governments and oil companies dither is another year that other countries and regions make headway on emerging and established ETS or targeted carbon. The clock is ticking-loudly.

Subsidies—going, going, gone?

Middle Eastern governments' initial attempts at creating price stability during the colonial era and after independence quickly evolved into gross overconsumption. MENA is home to 5.5% of the world's population and 3.3% of its GDP, yet it accounted for a staggering 48% of its energy subsidies, according to a World Bank report. Adversity has helped focus minds. Iran's financial woes spurred by Western-imposed sanctions prompted Tehran to introduce the Targeted Subsidy Reform Act in 2010, which provided a rough roadmap for subsidy cuts to spread across the region. Falling oil prices from mid-2014 helped the oil-rich Gulf as it started to change tack from January 2015. The reforms could not have come soon enough. For example, the cost of the UAE's petroleum subsidies totalled $7bn a year and were only part of wider energy subsidies that totalled $29bn a year—6.6% of GDP—before the country stopped fuel subsidies on 1 August 2015. Governments and state-owned oil companies' bid to cushion the thinning wad of petrodollars means ongoing subsidy cuts will be followed by a sales tax in several Gulf states from 2018, with talk of income tax for foreign residents.

The bottom line is that, Gulf states blessed with sunshine and wind as abundant as its oil and gas, the region is starting to plot a cleaner post-oil future.

ONES TO WATCH

MENA: End of the beginning for Saudi anti-corruption case?

Sectors: all

Key Risks: all

Between 26 and 28 January 2018, several high-profile figures including Prince al-Waleed bin Talal and TV broadcasting executive Waleed al-Ibrahim were released from detention in the Ritz-Carlton hotel in Riyadh in Saudi Arabia in a sweeping anti-corruption campaign launched by Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman in early November 2017. Announcements by Saudi officials and the Attorney General that several key accused businessmen agreed financial settlements with the government cannot be confirmed. Those announcements contradict statements saying a number of the accused businessmen were innocent, as officials said any one found innocent would not need to reach a financial accommodation with the government. Some of those detained have reportedly been moved to al-Ha’ir high-security prison and are due to stand trial on unconfirmed charges. Charges could be announced soon, although it is unclear whether the trials will be conducted publicly to provide transparency.